This is a companion discussion topic for the original entry at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jiSAB2VFW2I

Script

Karl Popper is one of the few recent philosophers to develop big, original ideas. He explained how intelligence, learning and science can work. The key is an evolutionary process that corrects errors. He proposed a solution to the problem of induction, refuted justificationism, and embraced fallibilism.

Popper lived from 1902 to 1994 and worked in academia. He published many books and papers. His philosophy is called Critical Rationalism, or CR for short. CR focuses on topics like knowledge, science and rationality. I’ve tried to improve and build on CR with my own Critical Fallibilism.

CR advocates fallibilism, which says that no matter how confident we are, we can never have a 100% guarantee that an idea is true. We could always have made a mistake. And mistakes are actually common. To deal with our fallibility, we should focus on finding and correcting errors. We can always keep making progress rather than reaching infallible perfection and being done.

This is a companion video for my CR overview essay. The essay is linked below and visible on the right.

Evolution

People think of evolution as a biological theory about plants and animals. But evolution is really a theory about replicators. Evolution explains where complexity or design can come from. A wolf appears designed to be good at hunting, so there’s a mystery there about what caused that, which isn’t present when you look at a rock. Evolution’s answer is replication with variation and selection. That isn’t CR’s unusual claim; you can find it in the writings of mainstream biologists like Richard Dawkins.

CR says that the appearance of design, or of complexity that fits a purpose, is knowledge. So evolution addresses the central problem in epistemology of how knowledge is created. People often assume that evolutionary epistemology is a metaphor, but it’s entirely literal. Ideas are replicators which are varied and selected within a brain.

In biology, it’s well known that no one has ever come up with a reasonable alternative to evolution. It’s really hard to think of anything else that might work. The few alternatives are bad explanations like intelligent design or spontaneous generation.

CR says the situation in epistemology is the same: there are no reasonable alternatives to evolution and there never have been any. And if there were any alternative theory of how knowledge is created, besides evolution, then it would also apply to biology. If induction can’t provide a possible explanation the origin of species, then it’s wrong, because the origin of the species is a matter of the creation of new knowledge.

Critical Thinking and Discussion

So what should we do if we learn by evolution? Critical thinking and critical discussion. We need to look for errors and try to correct them. In biological evolution, the errors often lead to death. In thinking, we need to metaphorically kill our errors with refutations and change our minds.

There’s also a logical asymmetry between criticism and supporting arguments which makes criticism superior. A single error can show an idea is wrong, but thousands of supporting arguments can’t prove it’s true. This is well known with counter-examples: the claim “all ravens are black” would be refuted by observing one orange raven. But observing thousands of black ravens doesn’t tell you that all ravens are black, nor does it give that claim a high probability. So criticism can be very logically effective, while it’s unclear that support does anything useful in terms of logic.

CR says to look for errors. We should prefer ideas we can’t find anything wrong with over ideas that we know errors with. One of the main problems in epistemology is how to evaluate ideas and decide which are correct or good, and CR’s critical approach provides an answer.

We also have to generate ideas. So CR calls its method “conjectures and refutations”, which means coming up with ideas and also trying to find errors in them. It’s basically brainstorming and critical thinking.

Justification

CR is a minority viewpoint. It’s only decades old instead of millennia. The most popular view tries to decide which ideas are good by looking for positive support. Popper calls this justificationism because of the widespread claim that knowledge consists of justified, true beliefs. Justification and support are synonyms.

CR says all three words in “justified, true belief” are errors. Criticism is logically better than justification like we saw with ravens. The demand for knowledge to be true is infallibilist. And the demand for knowledge to be a type of belief implies that a wolf’s genes don’t contain any knowledge since genes don’t have beliefs. It also means that books don’t contain knowledge, since books don’t believe anything. While that viewpoint is popular with academic philosophers, many people advocate justification without insisting on the true and belief parts.

Criticism works well because it deals with an important logical relationship called “contradiction”. Criticisms can contradict the ideas they criticize. Not all criticisms use contradiction, which is one of the improvements I’ve developed: I said to stop using weaker criticisms that don’t contradict the idea they criticize.

Justification doesn’t work well because it doesn’t use an important logical relationship. Supporting evidence for a theory is merely consistent with it. Consistency just means there isn’t a contradiction. But the absence of a contradiction doesn’t actually tell you something is good or true. Every false idea has vast numbers of things that don’t contradict it, but it’s false anyway because of something else that does contradict it.

Fallibilism

Fallibility means we can always be mistaken even when we’re really confident, mistakes are pretty common, and we can’t get guarantees that ideas are true. We also can’t have a guarantee that an idea has a low probability of being false.

Justificationism can be viewed as an attempt to fight against fallibility. The goal of justification is to prove ideas are true or reduce the possibility of ideas being false – in other words to make ideas infallible or less fallible. Popperians accept our fallibility and focus on error correction.

Induction

Induction is a popular version of justificationism that’s over 2,000 years old. Modern versions focus on learning from patterns in evidence. Finding patterns and accumulating more evidence is claimed to support ideas.

There are mistakes here. It has the logical problems with justification that I explained earlier. Its focus on data neglects conceptual explanations. And it’s similar to intelligent design.

The problem with intelligent design, as a rival theory to biological evolution, is that it presupposes knowledge. It’s supposed to explain where knowledge comes from, but it assumes a designer who has the knowledge needed to design the animals. It fails to explain how that knowledge could be created starting with no knowledge.

Induction presupposes an intelligent person who can find patterns in data. It relies on knowledge instead of explaining the origin of knowledge.

Finding patterns in data is hard and requires lots of intelligence and critical thinking to do well. The difficulty is that there are infinitely many patterns compatible with any finite data set. So the hard part isn’t finding a pattern but figuring out which patterns matter. Inductivists tend to rely on their intelligent intuition to guide them because no theory of induction gives step by step directions for choosing between any set of patterns.

Claiming the future will probably resemble the past ignores the issue of in which ways the future will resemble the past. Claiming that patterns tend to hold over time ignores the issue of which patterns. No matter what happens, some patterns hold and some don’t. The future always has similarities and differences from the past.

Inductivists have also failed to define what counts as a pattern or what counts as two things being similar.

There are some attempts to make induction work using probability. CR criticized them but I don’t have time to cover them now.

Interpreting Observation

CR also says to consider how observation itself works. We interpret the data from our senses using our ideas rather than just seeing raw data. Our interpretations may be mistaken, so our observational evidence is all fallible. This is another difficulty facing induction. CR handles the fallibility of everything well because its basic method is to look for errors, which is an appropriate way of dealing with fallibility, since fallibility means the capability to make errors.

Decisive Criticism

We can summarize CR’s rejection of justificationism by saying that non-contradiction isn’t an effective logical tool. Contradiction works better. So CR advocates negative arguments and rejects positive arguments.

My philosophy, Critical Fallibilism, makes an improvement to CR here. CR accepted the common view that arguments can be strong or weak. But what is a weak criticism? It’s a criticism which doesn’t contradict what it’s criticizing.

So I concluded that we should use decisive criticisms that make use of contradiction. Criticisms that merely try to weaken an idea, without contradicting it, are no better than justifications.

Logical Concerns

We could make a mistake when determining that two ideas contradict. Our knowledge of contradiction is fallible. How does CR handle this? It focuses on errors that someone has found, not just potential errors. Fallibility means you may look for errors anywhere because nothing is fully safe. But you have to actually find something you think is an error before you reject an idea.

Another question people have is how to deal with someone who keeps making up new ideas every time you refute one. It’s pretty easy to make up an infinite stream of ideas if you aren’t concerned with quality. A solution is criticizing categories of ideas instead of individual ideas. If someone is mindlessly making up a series of ideas following some simple pattern, then you can criticize the pattern.

For example, someone might claim an alien came and shot you with a hallucination ray gun, and that’s the real explanation for the outcome of your science experiment. If you refute it, he might then come up with a new idea: two aliens came and shot you with a hallucination ray guy. If you refute that, he could claim it was three aliens. He could say four next time and keep changing the number indefinitely. The solution is to criticize all arbitrary explanations of experimental results in terms of alien ray guns. If your rebuttal depended on the specific number of aliens, and didn’t apply to other numbers, then it would actually be reasonable to propose five aliens since it’s not refuted yet. If your criticism lacks the generality to cover five aliens, that is a weakness in your thinking which you should thank him for bringing up.

Conclusion

To learn more, you can read my full essay, linked below. Karl Popper wrote books about Critical Rationalism, but they take a long time to read, so I’ve also linked my recommendations for the best parts to read. And you can find my free essays at criticalfallibilism.com.

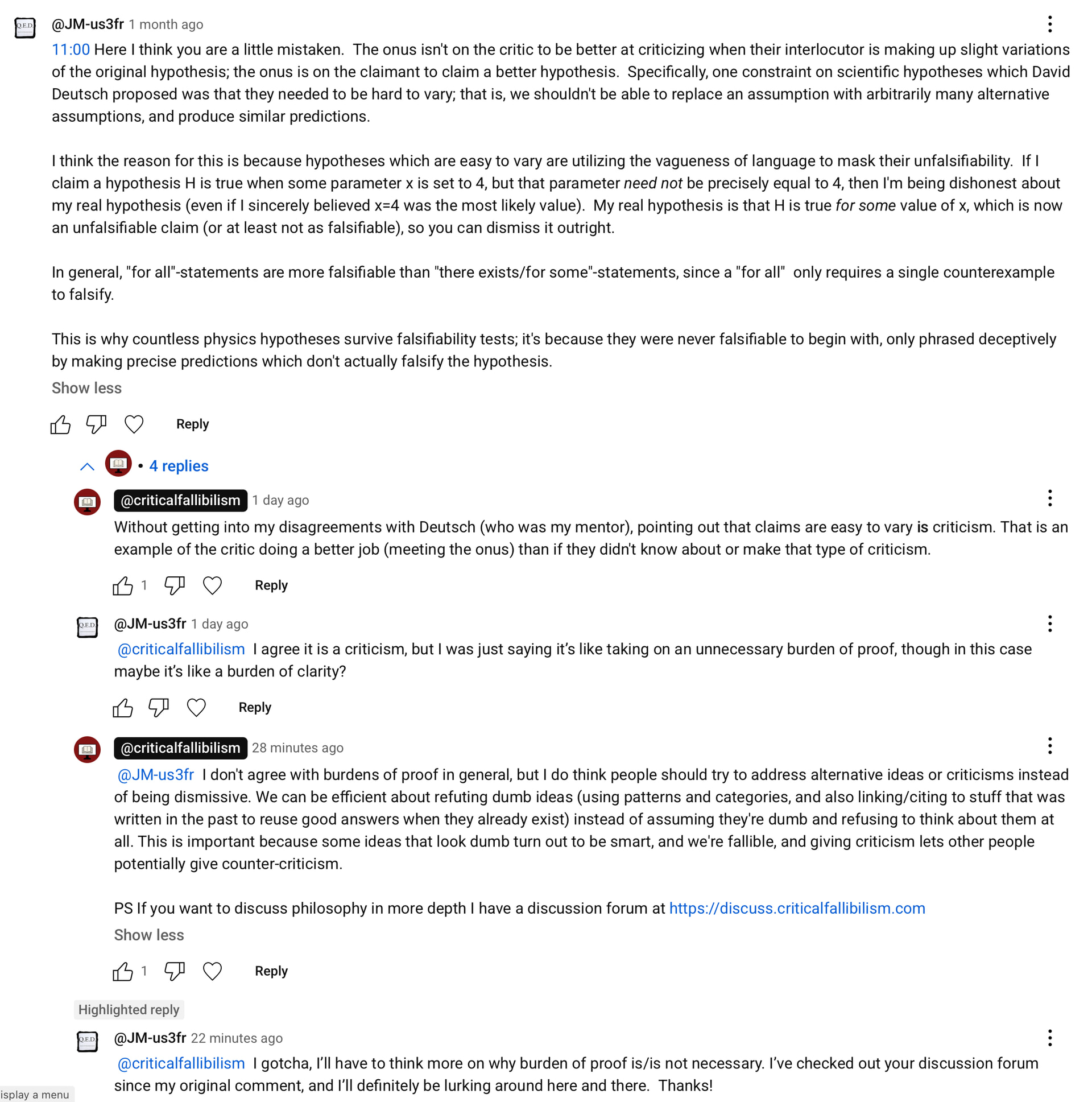

JM-us3fr in YouTube comments wrote (not his full comment):

11:00 Here I think you are a little mistaken. The onus isn’t on the critic to be better at criticizing when their interlocutor is making up slight variations of the original hypothesis; the onus is on the claimant to claim a better hypothesis. Specifically, one constraint on scientific hypotheses which David Deutsch proposed was that they needed to be hard to vary; that is, we shouldn’t be able to replace an assumption with arbitrarily many alternative assumptions, and produce similar predictions.

I replied:

Without getting into my disagreements with Deutsch (who was my mentor), pointing out that claims are easy to vary is criticism. That is an example of the critic doing a better job (meeting the onus) than if they didn’t know about or make that type of criticism.

Unfortunately, YouTube only inconsistently sends me email notifications about new comments. For substantive discussion, I recommend using this forum.

Hmm. Have you ever considered doing something like this:

He was able to make a clickable link to his merchandise in a pinned YouTube comment. Maybe put a link to the forum discussion board on the YouTube video and pin it? I mean there is a cost to post on the forum, but you could put a disclaimer for that (and also share how you think the forum is a better place for discussion).

My YouTube descriptions link the CF website which has “Discuss” in the header and footer.

People don’t always read the description and the people who comment on the vid are the ones you most want to come here and probably the people who most want to post here too. I think Eternity’s idea is good.

I pinned this wording on a couple videos:

If you’d like to discuss this in more depth than YouTube comments, join the Critical Fallibilism discussion forum at https://discuss.criticalfallibilism.com

Taking suggestions/feedback on the wording.

Lots of people read comments but don’t comment themselves. It would be a good starting point for them (and the ones who want to comment) to get a link to the topic for that specific video. They’re at the moment interested in that specific topic and might like the comments made by us regulars.

I think it’s fine to leave out the entry fee since they’ll see it once they arrive and they can read the forum without it.

Saying there’s more activity on the forum than yt comments would be good but maybe too wordy. I think the same about saying why the discourse is better than yt comments like @Eternity suggested, would be good but maybe too wordy.

Oh yeah linking the specific video has to be done manually each time after the forum post gets auto-generated but I can do it sometimes. I changed the pinned comment for this video to:

Here’s the essay: https://criticalfallibilism.com/introduction-to-critical-rationalism/

Discuss this video at the CF discussion forum: https://discuss.criticalfallibilism.com/t/critical-rationalism-introduction/2023