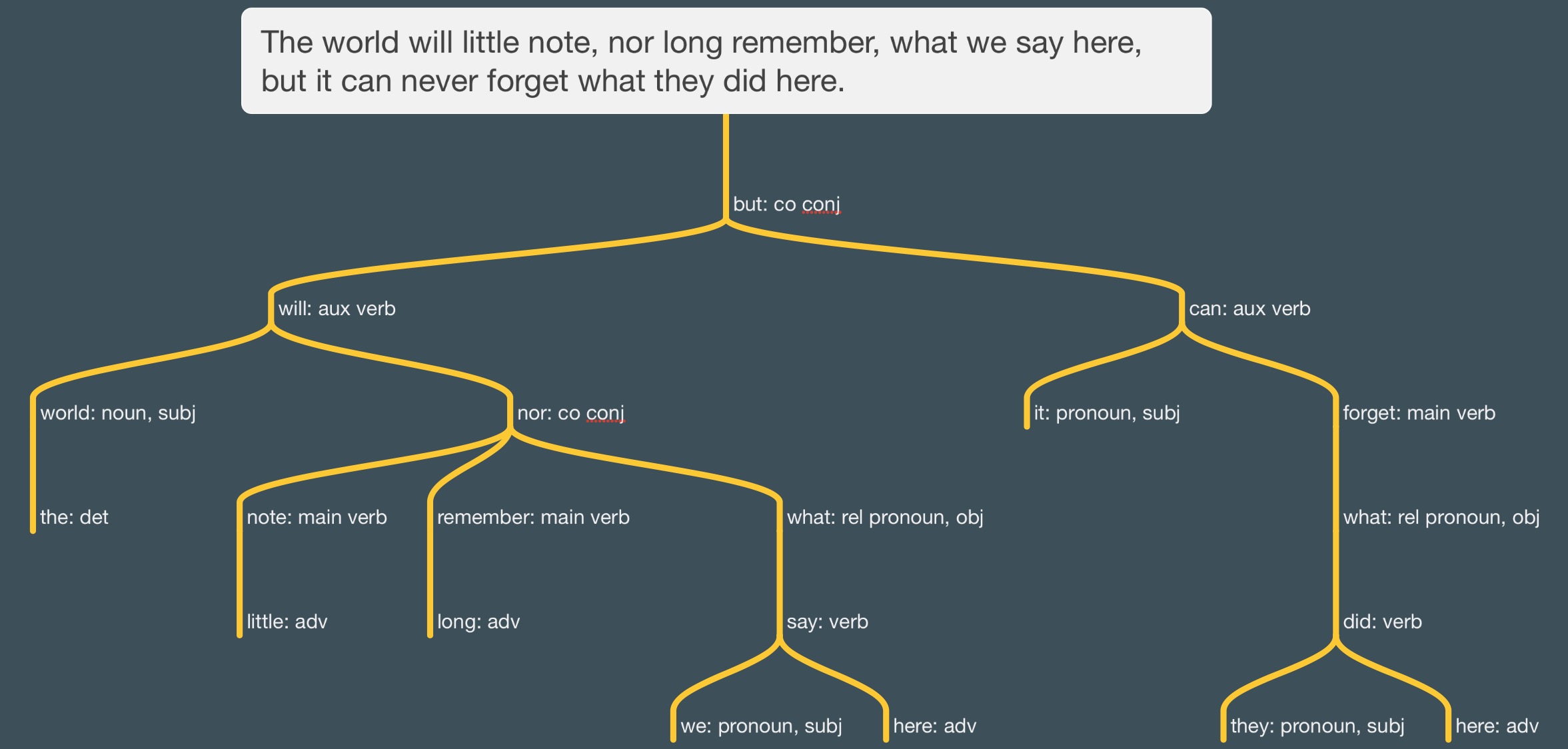

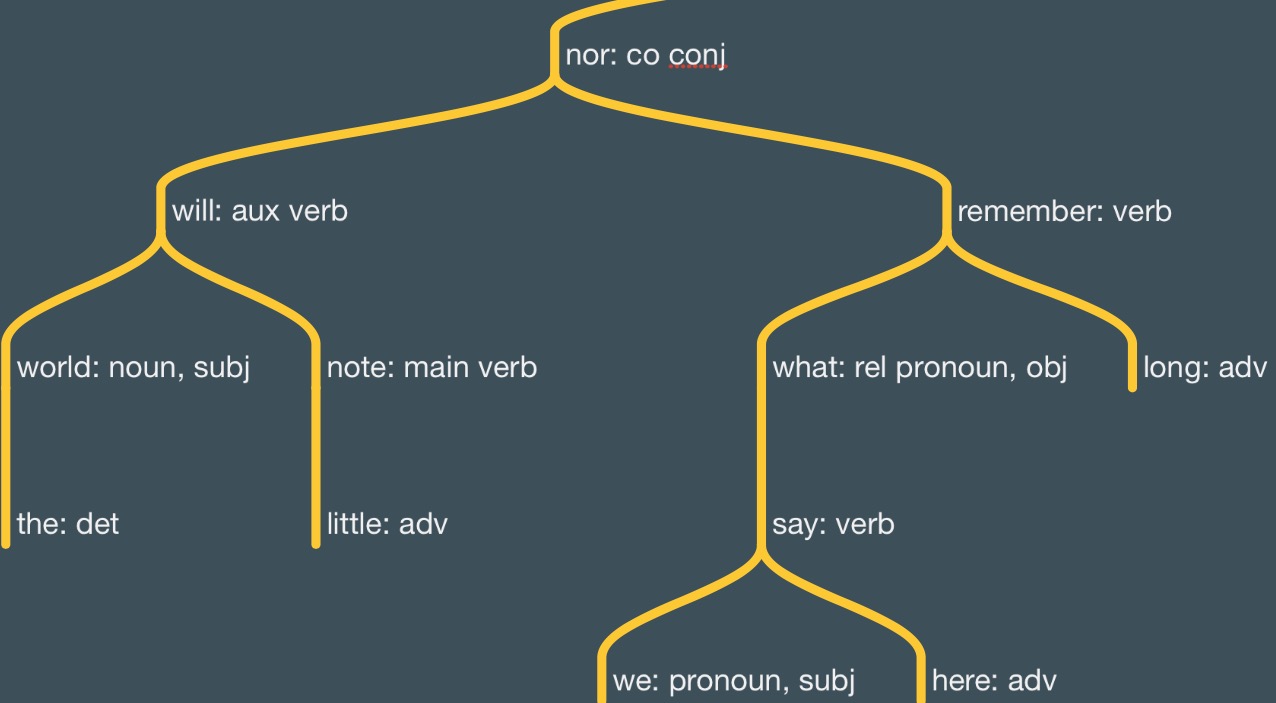

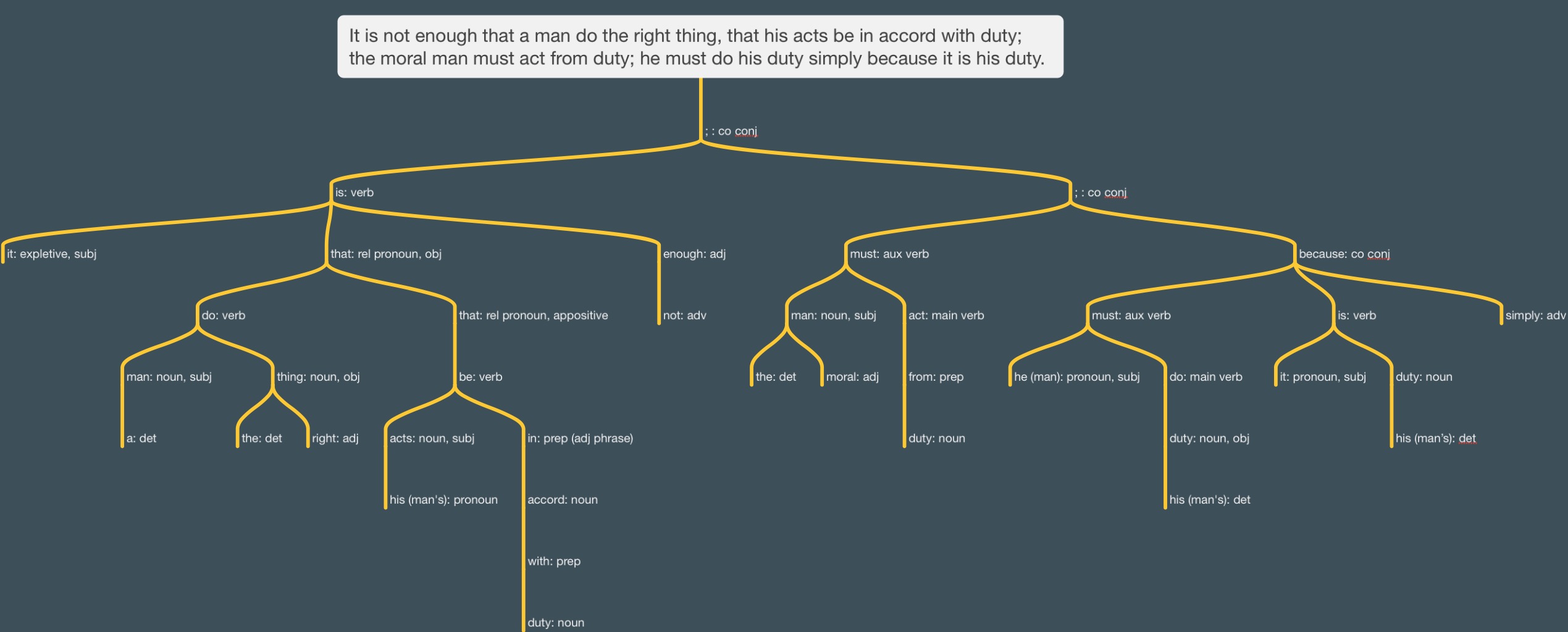

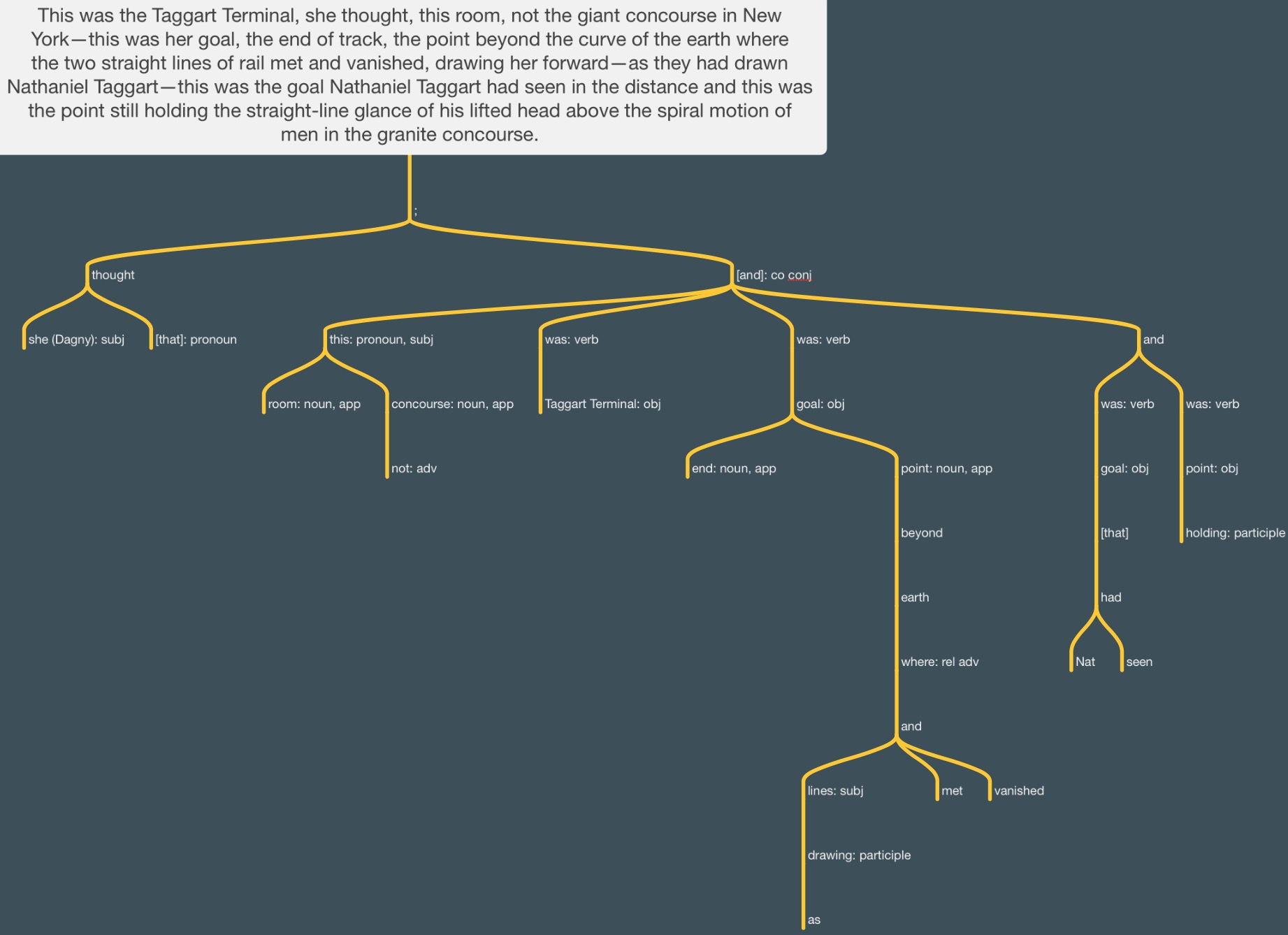

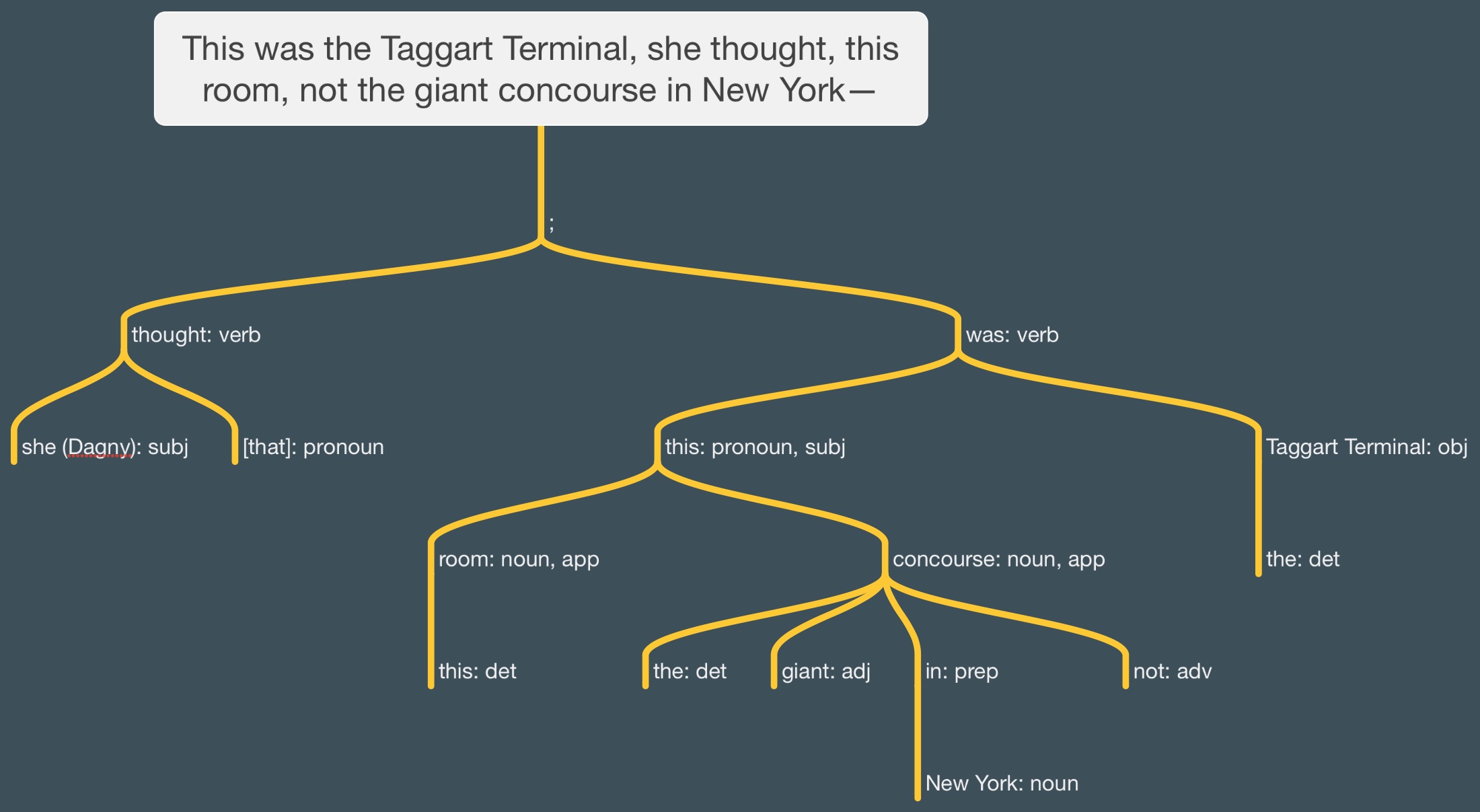

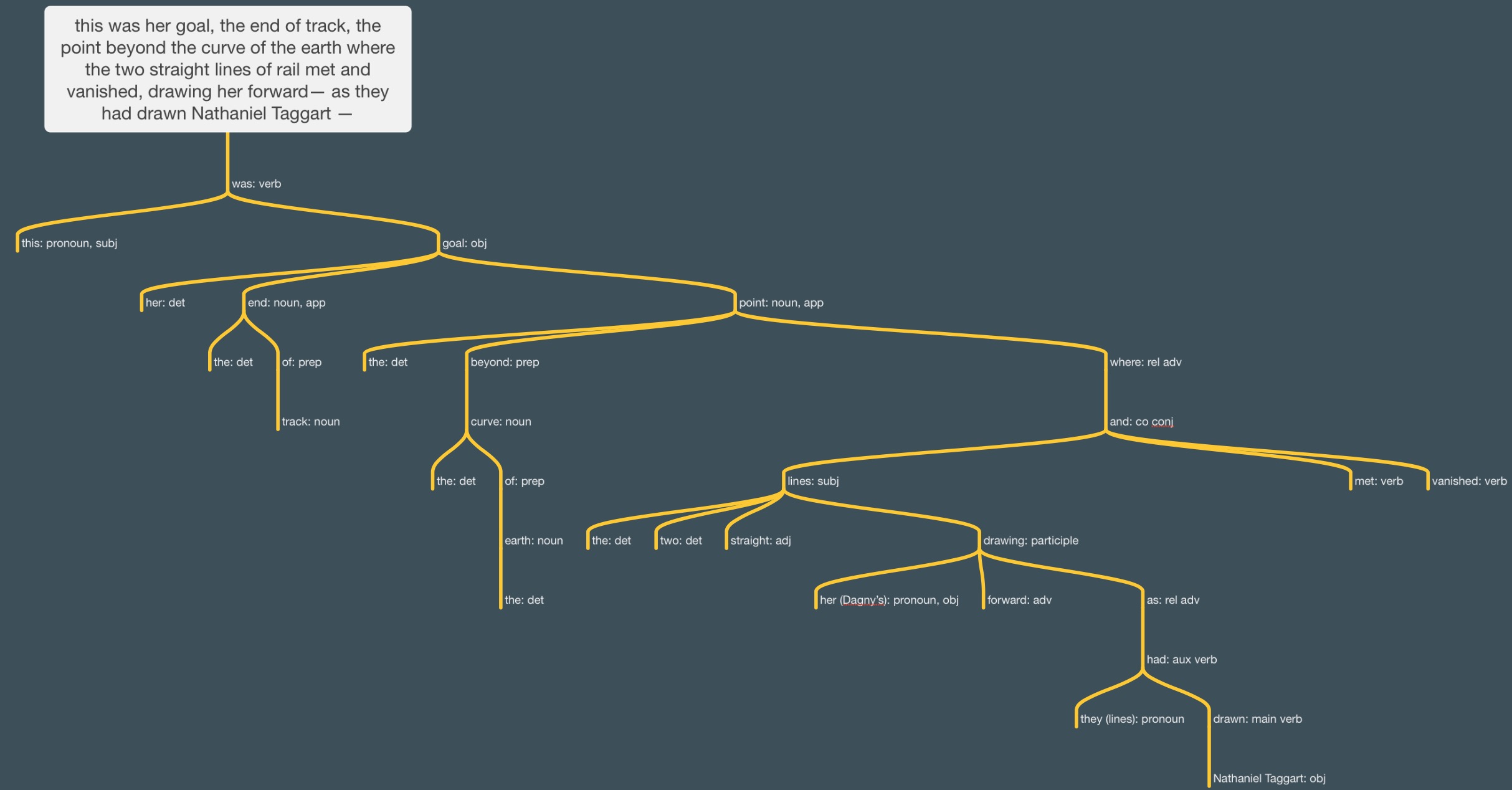

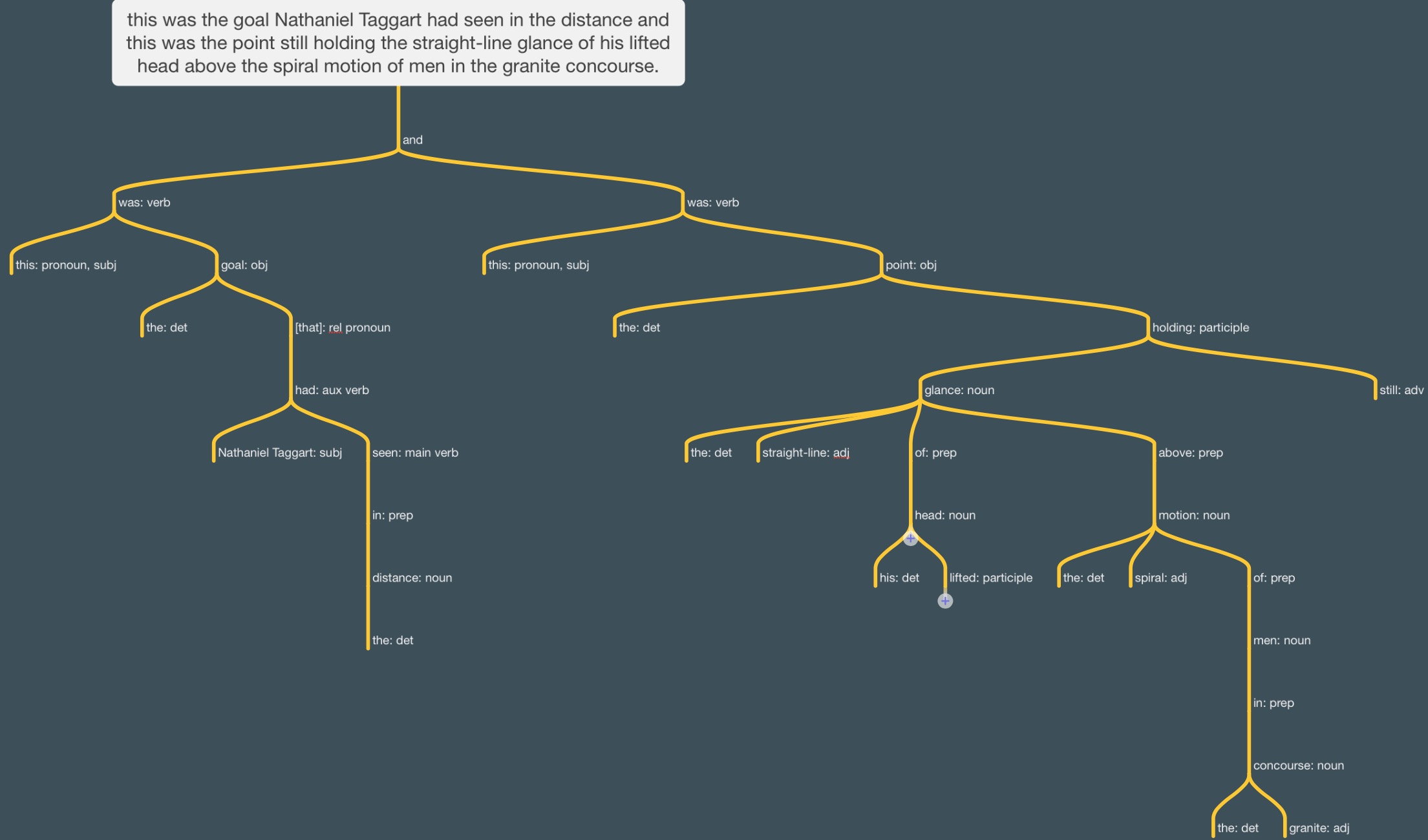

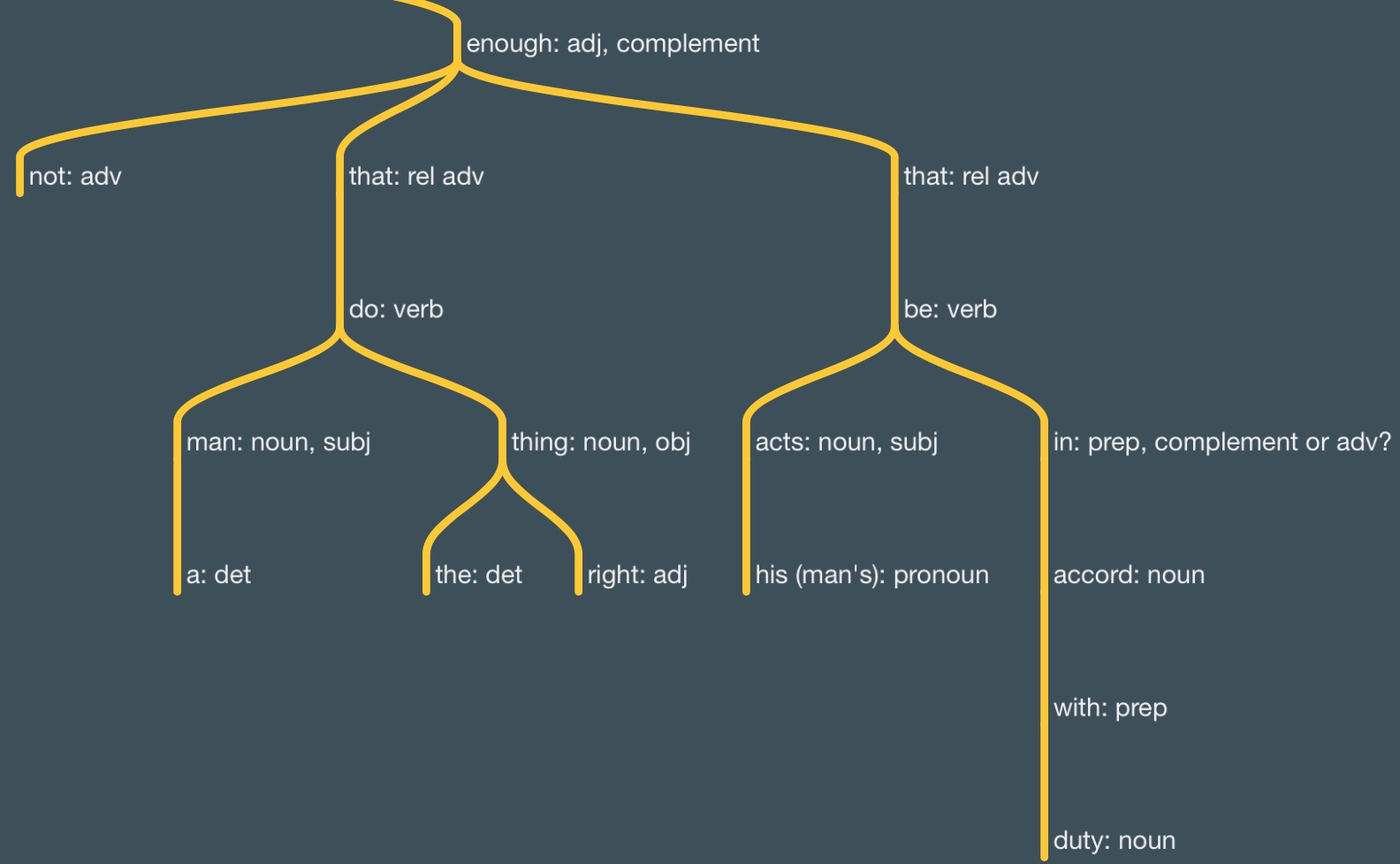

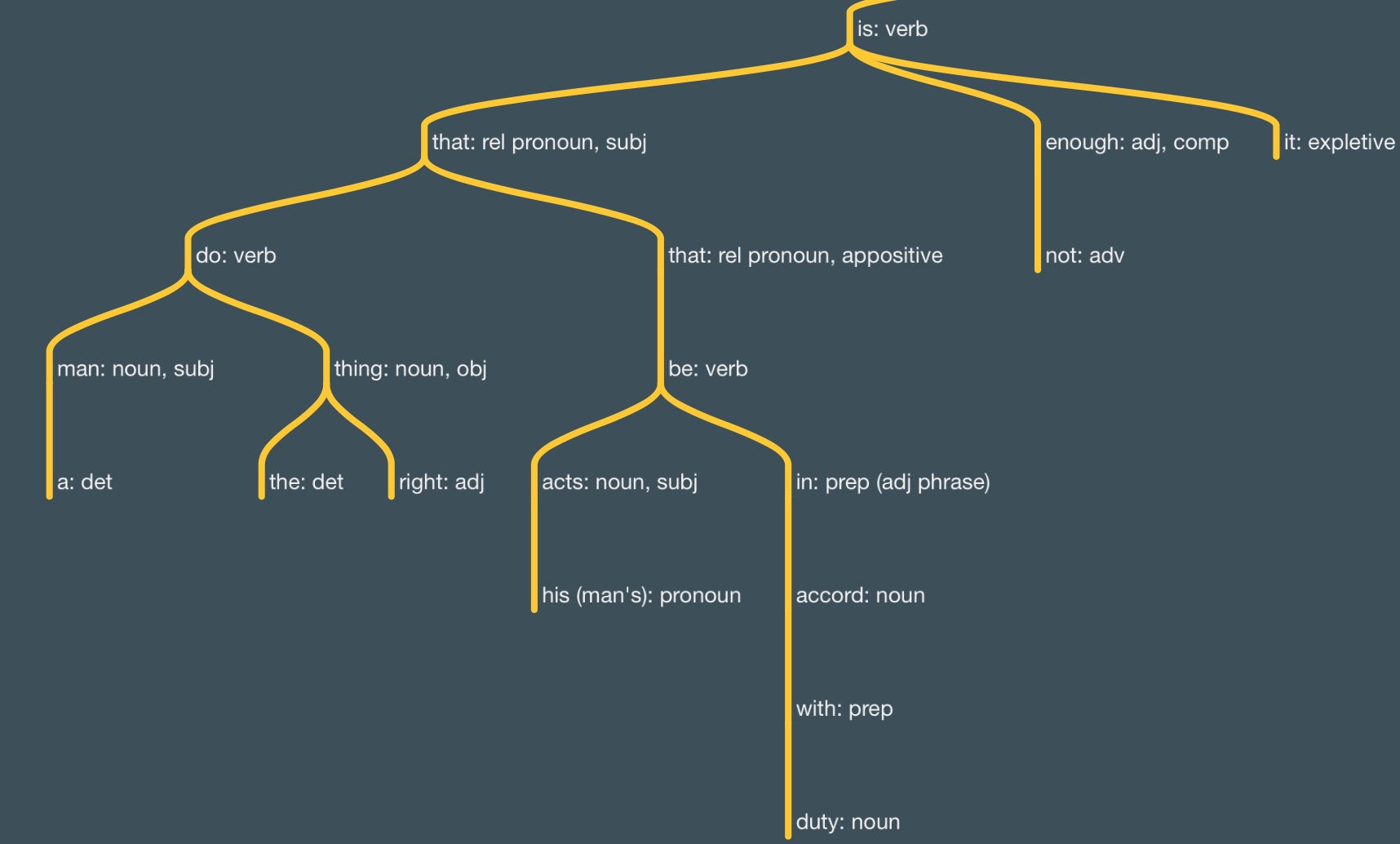

First I watched the grammar tree video for 37 minutes. I liked the part about relative adverbs/pronouns and how to view subordinating conjunctions. I think I’ll rewatch that part. There were some things I didn’t fully catch. The rest was reading Peikoffs course and doing a bit of the exercises.

Notes on Principles of Grammar:

I’m writing the notes to think about what I learn. The notes weren’t written to be read by others, so they might be hard to understand. I had one question at the end which I couldn’t answer myself.

ch. 1

Sentences, Fragments and Run-ons

four types of sentences:

- declarative: fact is the case

- interrogative: question

- imperative: order

- exclamatory: “phew!” “aha!”

concept not the same as “complete thought”. a single word is a concept but not a sentence (except “Stop.” and such).

And of course, the key word there is “self-contained,” because if I just say “is open,” that’s not a thought yet, it’s not self-contained, it doesn’t stand by itself. But if I say “The door is open,” then I’ve got a thought.

why isn’t “is open” self-contained? I feel like it’s similar to finite vs infinitive. “the door is open” is limited to some door and tells when it’s open, it’s specific, there aren’t endless possibilities like with “is open”, what is open? could be anything. so in a sense it isn’t self-contained and complete because we can’t think of all the possibilities, we can’t complete that thought. we can use “infinite” things (concepts) in sentences as building blocks, but there has to be some specific sense to it for us to think about it.

sentences express division of thoughts. separates thoughts into neat little boxes. adding in a bunch of extra thoughts separated with commas (as I often do) breaks the definition of a sentence and is therefore not even a bad sentence.

I knew a bit about this already and it has helped me break things into sentence. I think “is this a single thought?”.

subject and predicate

something to talk about + something to say about it = complete thought.

with only something to talk about you just name the thing and what about? what would be the point? there is no content, only a topic. and only something to say, it has to be about something otherwise there is no context, nothing to relate it to. the closest would be a general feeling about everything or life in general like “bad” or “exciting”.

predicate = state, affirm, assert

Many are the days I met him.

seems more poetic than regular english to me.

phrase

grouping. multiple ideas/things combine into one thing. has unity but not a complete thought. complete thoughts have unity, but unity is not enough to make something a complete thought.

isn’t “was jumping up and down” also a phrase? because “up and down” is a modifier on “was”. so that’s the predicate, and the predicate is a phrase, it’s unity is telling the action or linking in the sentence. so “up and down” is a sub-phrase of the phrase “was jumping up and down”. “was jumping” works as a phrase but we didn’t include the whole phrase.

clause

clause has the grammatical components of a sentence: a subject and a predicate. but it’s not a sentence because it’s not a complete thought. so the difference is conceptual, not just mechanical grammar rules. or are there always types of words like “when” to make something from a sentence to a clause?

exercises

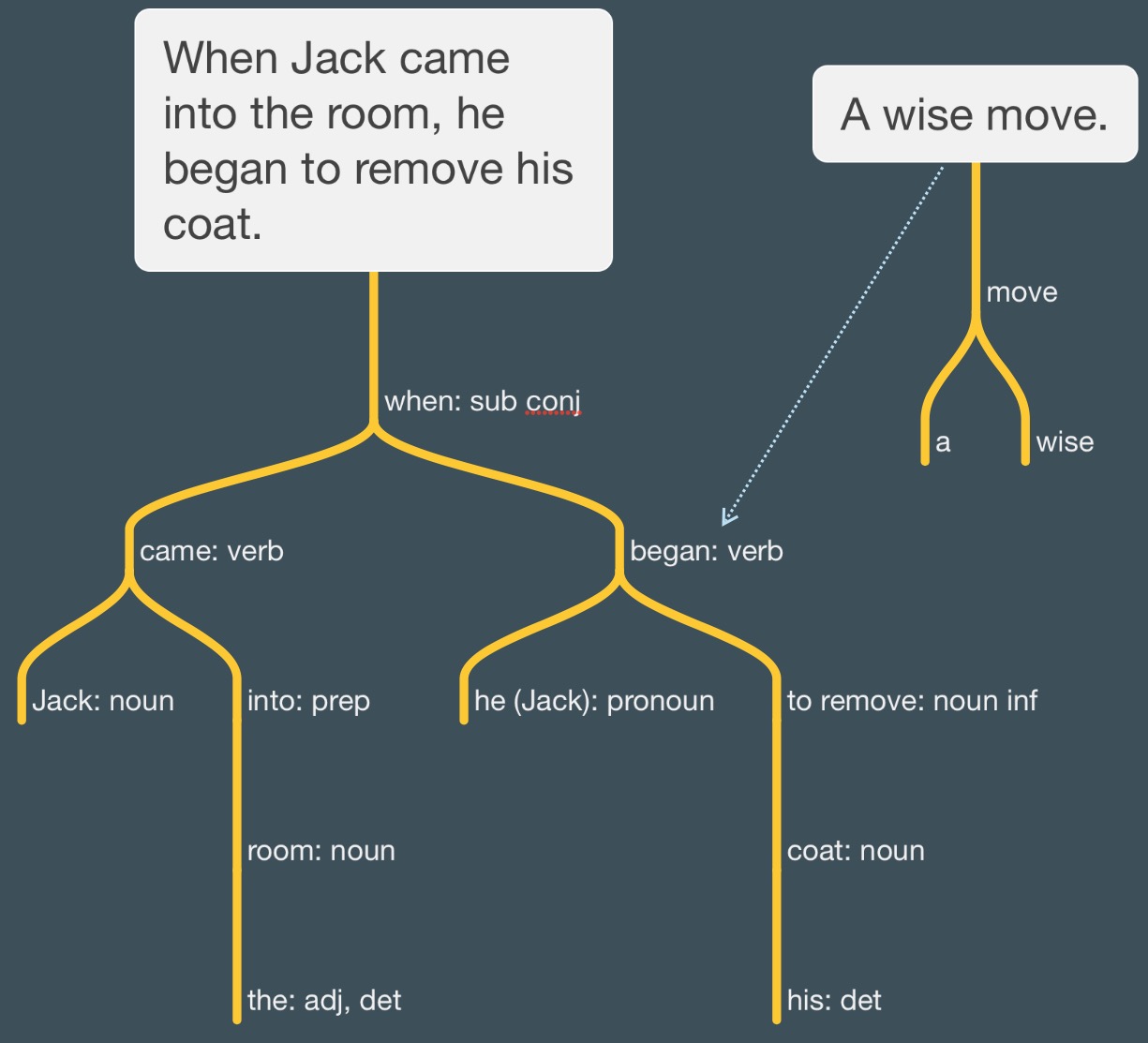

When Jack came into the room, he began to remove his coat.

- when: sub conj

- came: verb

- began: verb

- he (Jack): pronoun

- to remove: noun inf

when {Jack came <into <the room>>}, {[Jack] began <to remove <his coat>>}

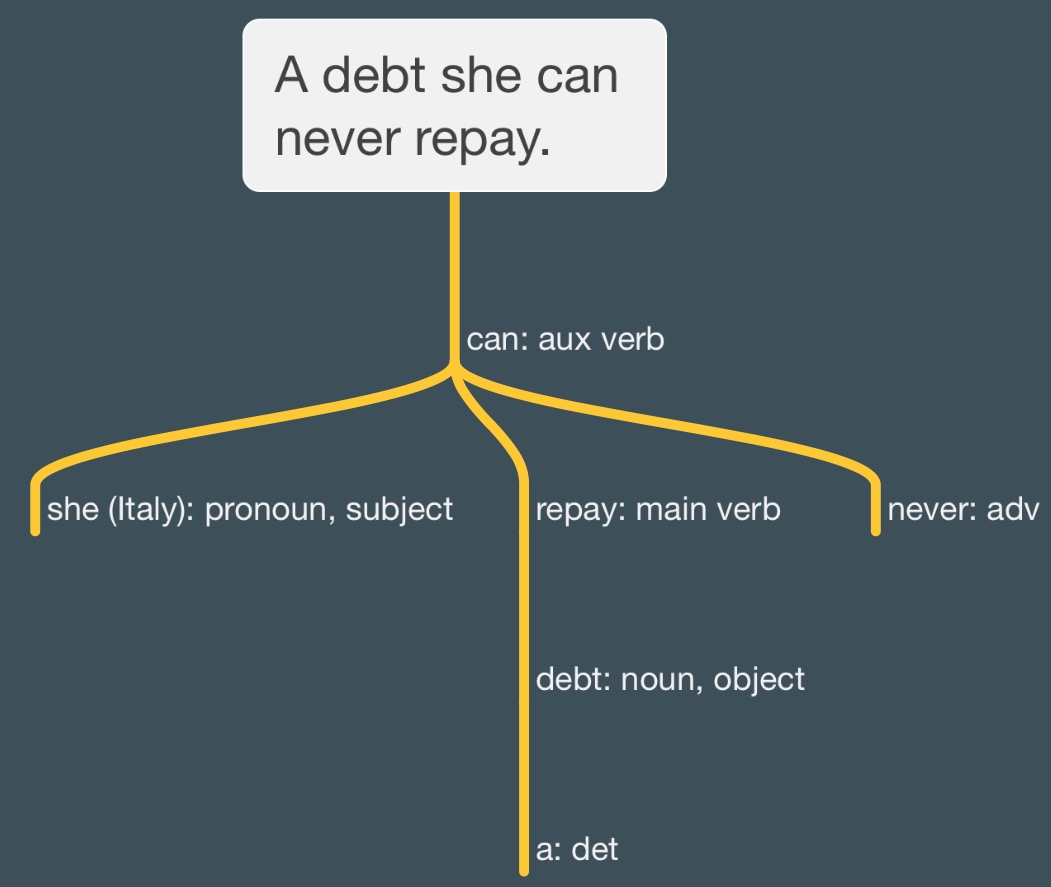

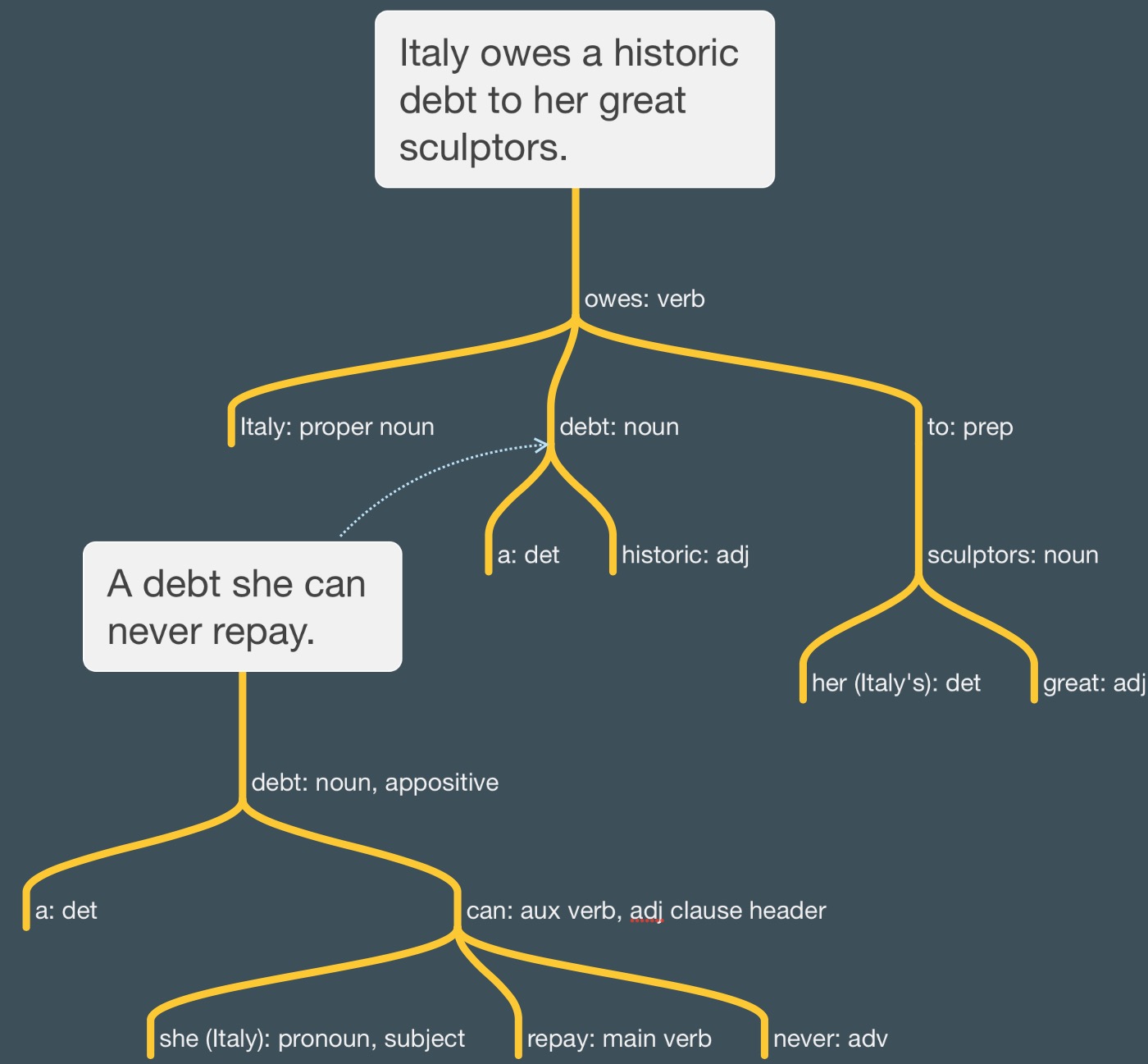

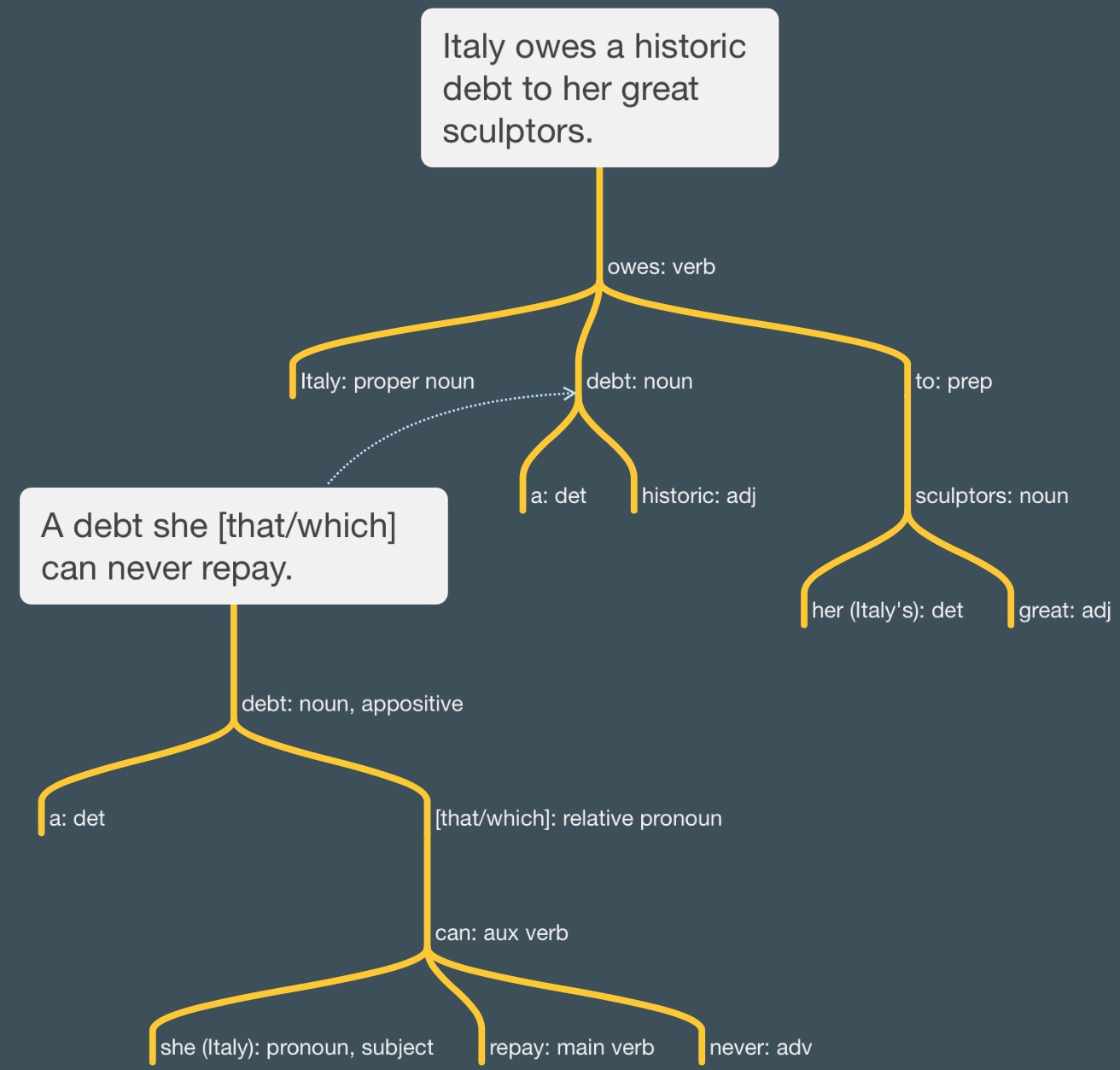

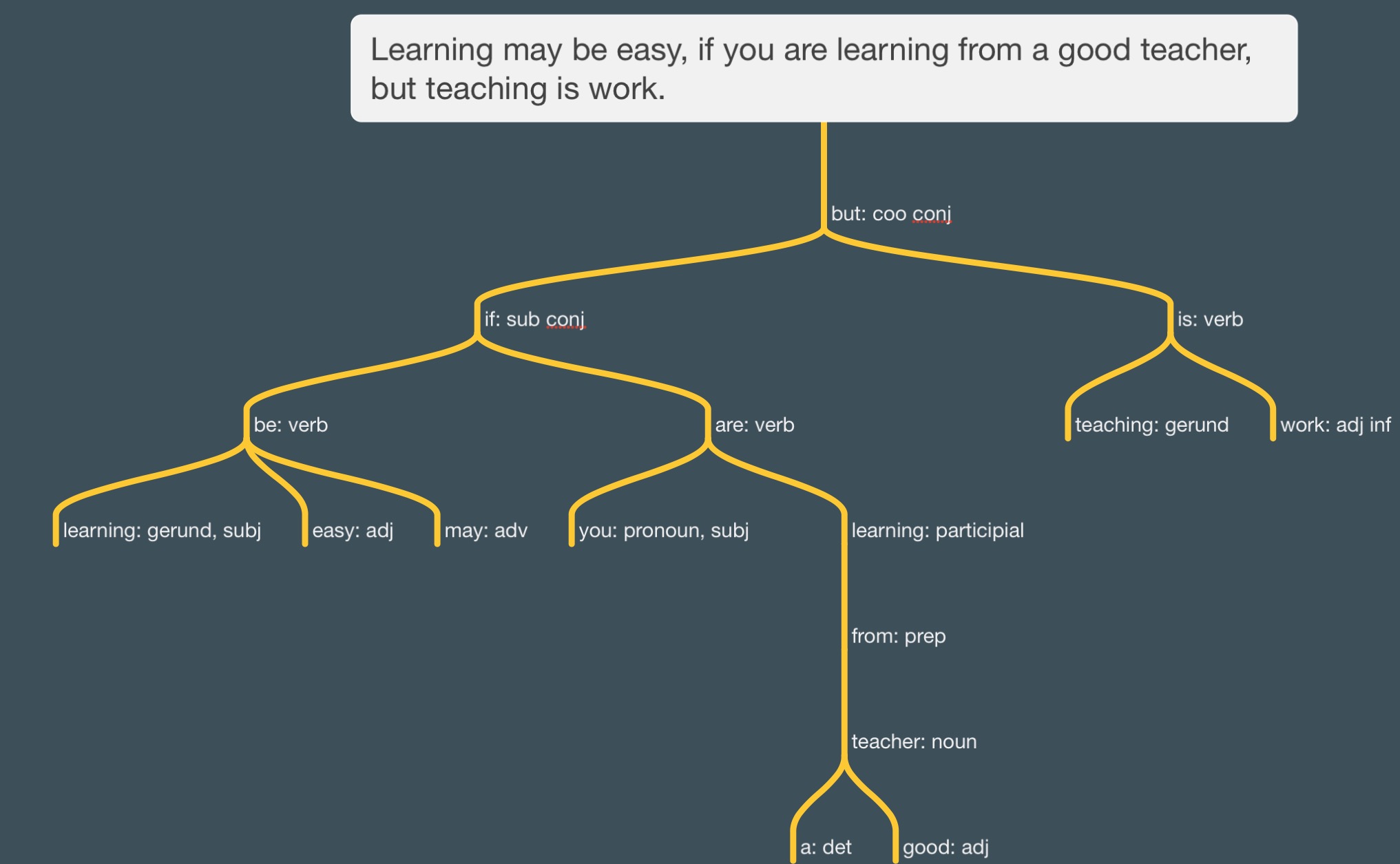

Learning may be easy, if you are learning from a good teacher, but teaching is work.

- but: coo conj

- if: sub conj

- be: verb

- learning: gerund

- easy: adj

- may: adv

- are: verb

- you: pronoun

- learning: gerund

- from: prep

- is: verb

- teaching: gerund

- work: adj inf

{<learning may> be easy}, if {you are <learning <from <a good teacher>>>}, but {teaching is work}

subject/noun

things and concepts (states as well? are states included in concepts?)

only primary means of referring to an aspect of reality

therefore:

the subject […], will be a noun.

or pronoun. or other things that act like nouns. they’re all nouns in a sense. they share some characteristics.

predicate

“smells” and “seems” are linking verbs

no proverbs or verb-equivalents.

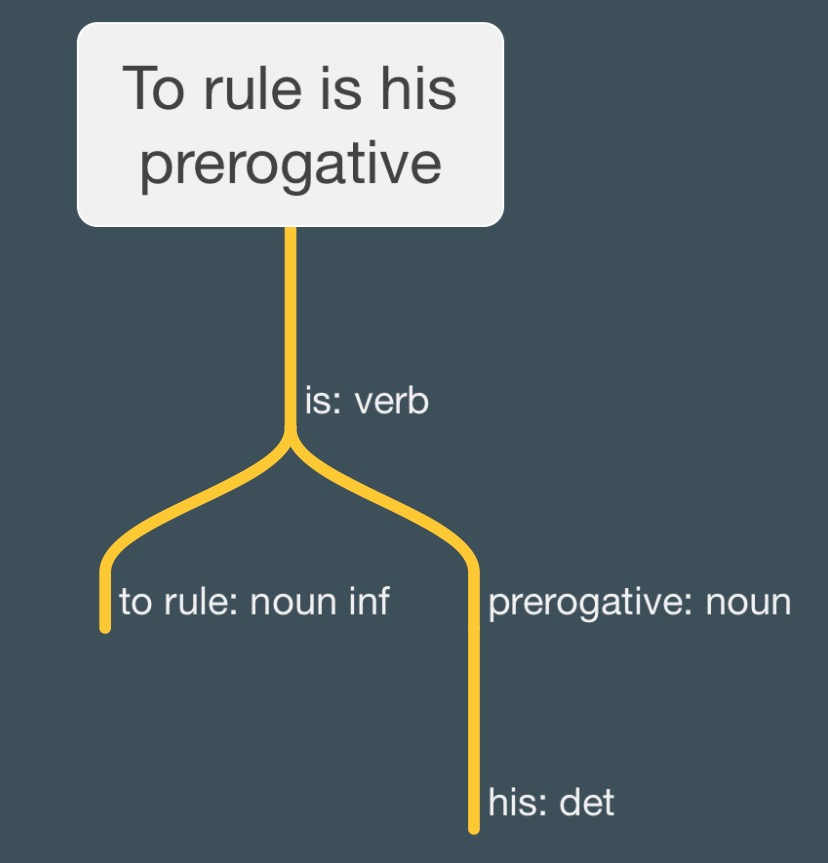

verbal

not the action actually happening, usually is the concept of the verb.

modifier

describe, limit or qualify.

adverbs functioning as conjunctions: “so”, “when”. I didn’t think of it like that. I just thought of them as adverbs. but it’s quite clear with “when” that it’s not just joining things, it’s also telling us about timing. so the extra thing it tells is like a modifier. Elliot said something about this in the grammar tree video.

I went home for dinner

I thought “home” would be a noun. I thought it was a kinda shortcut to leave out “to my” so that would be:

I went to my home for dinner

but that would be a prepositional phrase, so acting as an adverb, might as well just treat “home” as an adverb in itself.

oh, that was exactly what happened!

If you wanted to make it a noun, you’d have to say “I went to my home.” […] Originally it was a noun. So it’s a shorthand noun functioning as an adverb.

I think it help to understand what it used to be because it seems more in line with the rules. “I went home” seems more like an exception.

complement and object

Elliot mentioned objects were complements, but complements are not objects. objects are the sub-group. that makes sense since we can have action verbs without an object, but some action verbs require the object. otherwise it’s not complete, so therefore the object is a complement.

It was too close for comfort

initially I thought “for comfort” would modify “was”, but it makes more sense to modify “close”. It doesn’t make sense without the “too” though. is “too” a complement then? “it was close” and “it was too close” both work so “too” wouldn’t be a complement. actually “it was close for comfort” works, but feels a little weird. the meaning is totally different so I didn’t detect that it worked.

It says the mouse was darting up the wall. But strictly, it doesn’t say the mouse was darting up the wall; it says the mouse escaped.

because “escaped” was the only verb.

You can’t think to yourself, “Well, it really tells you how it escaped, because it escaped by just darting up the wall.”

that was what I thought to myself.

The form of the words requires you to interpret it that way

right, the grammar tells us how we should interpret it. this makes it more objective.

“She put a pie into the oven to bake.” “To bake” is a phrase, an infinitive, and what action does it describe? It’s the purpose of the action. Now, I know that it might seem odd that the purpose is an adverb and the mechanism is an adjective

I don’t understand what is meant by “the mechanism is an adjective.” I think “to bake” modifies “put.” we could add “in order” to get a prepositional phrase.

Project Notes

| Total time |

4:13 |

|

|

| grammar |

4:13 |

|

|

| \_meta |

|

0:09 |

|

| \_ watch grammar vidoes |

|

0:37 |

|

| \_ peikoff course |

|

3:27 |

|

| \\_ read and take notes |

|

|

3:07 |

| \\_ first try exercises |

|

|

0:20 |