Limiting Reason; Making Progress on Philosophy

(Quotation from Chapter 3 of How to Think Like a Roman Emperor):

If we wish to improve ourselves, Galen says that we must never relax our vigilance, not even for a single hour. How on earth do we do that? He explains that Zeno of Citium taught that “we should act carefully in all things—just as if we were going to answer for it to our teachers shortly thereafter.”16 That’s a rather clever mind trick that turns Stoic mentoring into a kind of mindfulness practice. Imagining that we’re being observed helps us to pay more attention to our own character and behavior. A Stoic-in-training, like the young Marcus, would have been advised always to exercise self-awareness by monitoring his own thoughts, actions, and feelings, perhaps as if his mentor, Rusticus, were continually observing him. Epictetus told his students that, just as someone who walks barefoot is cautious not to step on a nail or twist his ankle, they should be careful throughout the day not to harm their own character by lapsing into errors of moral judgment.17 In modern therapy, it’s common for clients who are making progress to wonder between sessions what their therapist might say about the thoughts they have. For example, they might be worrying about something and suddenly imagine the voice of their therapist challenging them with questions like “Where’s the evidence for those fears being true?” or “How’s worrying like this actually working out for you?” The very notion of someone else observing your thoughts and feelings can be enough to make you pause and consider them. Of course, if you occasionally talk to a mentor or therapist about your experiences, it’s much easier to imagine their presence when they’re not around. Even if you don’t have someone like this in your life, you can still envision that you’re being observed by a wise and supportive friend. If you read about Marcus Aurelius enough, for instance, you may experiment by imagining that he’s your companion as you perform some challenging task or face a difficult situation. How would you behave differently just knowing he was by your side? What do you think he might say about your behavior? If he could read your mind, how would he comment on your thoughts and feelings? You can pick your own mentor, of course, but you get the idea.

Bob (B): What do you think of the above?

Adam (A): My immediate reaction, especially to “Galen says that we must never relax our vigilance, not even for a single hour”, was that I thought of a scene in Atlas Shrugged, where one of the villains is going on a rant to one of the heroes. The villain says, in part:

Don’t look at me! You’re asking the impossible! Men can’t exist your way! You permit no moments of weakness, you don’t allow for human frailties or human feelings! What do you want of us? Rationality twenty-four hours a day, with no loophole, no rest, no escape?

B: Right. I think a lot of people would think in those terms - they imagine having to be vigilant against “temptation” all their waking hours, and imagine it’d be like living in a straitjacket.

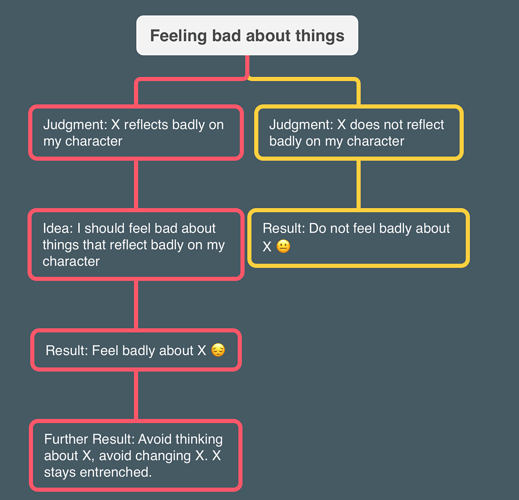

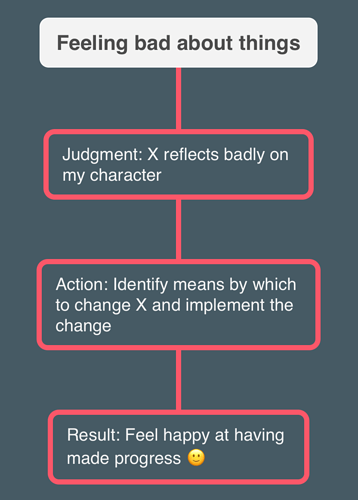

A: Right. Leonard Peikoff, in Understanding Objectivism, says something relevant in discussing emotions;

If you feel in general “Emotions prove something about me, and they’re out of my control; they’re a potential threat to my status as a moral person,” you’re still a thousand times worse off, because your emotions will naturally reflect something about you as an individual. They will be a constant source of fear, self-doubt, self-condemnation. And then you will begin to automatize the idea, “To be moral, I must repress myself,” and that becomes an issue of self-preservation. At a certain point, what happens is that you can’t take it anymore, and finally you “assert yourself,” and jump all the way to the emotionalist axis and say, “The only way to be myself is to say to hell with philosophy and principles,” and run wild. And I’ve seen that pattern many, many times.

B: Before we consider that, let’s go back to your Atlas Shrugged quote. What would be the meaning of a loophole, a rest, or an escape from reason, or rationality? What would you use in its place, and why would people want such a thing?

A: Maybe they’d want to go by their own personal preferences or whims or something like that.

B: And reason would threaten that how?

A: Well, take a concrete example. Suppose someone doesn’t have a job but would prefer to just watch TV instead of look for a job. If they could avoid reason somehow, they could do what they want to do instead of what they feel like they should do or have to do.

B: So a loophole or rest or escape clause from reason in that case would mean that the person doesn’t have to think about or deal with the argument that they have more urgent priorities than just watching TV right now?

A: Yeah.

B: That sounds irrational.

A: Right, but reason is basically what that person is trying to get away from.

B: But why?

A: Because they just want to watch TV.

B: According to their current ideas, that’s what they want to do. But if they thought about the issue some - if they thought about the long term consequences of their actions, what a wiser person might say about their situation, etc. - they might be able to persuade themselves that looking for a job was the best thing for them to be doing.

A: But most people are not very good at persuading themselves about things. So even if they managed to convince themselves to look for a job, they might feel bad about all sorts of things - about the state of their resume, about how an interview goes, about the sort of jobs they have to consider in their current position given their skills and background - and wish that they could just be watching TV instead.

I think being overly negative about their prospects in such a situation can help people rationalize their passivity. If you think “there’s no point in looking for a job, I’m not going to find anything, the economy is bad, nobody will give me a break”, then why bother searching for a job? So then you can just skip straight to watching TV.

B: Right. But “overly negative” implies a conflict between their view of their prospects and reality, which could come up and be pointed out to them if they engaged with reason.

A: Right.

B: So basically, according to your example, the purpose of trying to avoid reason is trying to avoid criticism so that people can do what they already wanted to do instead of feeling pressured to do stuff that reason might argue they should do.

A: Right.

B: That seems bad.

A: Yes.

B: So then, connecting this to the quote above from How to Think Like a Roman Emperor, we might expect people to be very resistant to having the vigilance described (whether they are assisted by a mentor or whether they are just relying on their own self-awareness and honesty) because they would experience it as enormously pressuring.

A: Right. Constantly monitoring and morally judging yourself would be excruciating for lots of people. They’d feel like they’re being asked to give up any pleasure or indulgences and be their own secret police.

I think that’s where the Peikoff quote comes in. People who are trying to engage with philosophy in some way, and who expose themselves to the criticism of others or to their own self-criticism, feel the need to “clean up” their moral situation and improve themselvs. But they still have lots of their old ideas. They need to engage with those ideas and gradually persuade themselves of replacements. But they don’t know how, or don’t want to, or something. So they hide and repress their old ideas as a shortcut. But the repression has a big cost, because there are parts of themselves that are being suppressed. And then eventually they explode and just give up on philosophy, like Peikoff talks about.

I think that lots of people like and see some value in parts of philosophy, but they see it as some kind of add-on to their existing life and existing values. They don’t want to have to make fundamental changes — to what sort of person they are, to how they engage with the world — in order to engage with philosophy. They want it to be something that fits within their existing life - like a hobby - instead of something that fundamentally reshapes their life and who they are. They want philosophy to fit inside neat little boundaries instead of spilling out everywhere. That’s what I think wanting an escape clause or whatever is about - they want to be able to limit philosophy and turn it off sometimes.

B: One of the things rational philosophy talks about, though, is the importance of intellectual consistency, of having integrity, especially with regards to the use of reason itself. So you can’t actually treat philosophy - rational philosophy, anyways - as a mere hobby without directly contradicting philosophy. That makes philosophy different than lots of things, which can fit into a “hobby” slot in people’s lives well. And it might be possible to evade this fact about the nature of philosophy for a while, but I think that the pressure will generally build up for people, especially to the extent they make any serious effort to apply philosophy rigorously to their life. Note that when I talk about philosophy here, I’m talking about various traditions of rational philosophy that do seek to offer people an integrated view of existence and way of life. There are types of philosophy that you could use to sound clever at cocktail parties or whatever, but that’s not the sort of thing I have in mind. Note also that I’m not saying that people can’t take bits and pieces of rational philosophy and improve their lives with it - I’m saying that to the extent they are trying to engage with rational philosophy in a somewhat serious way, they’re going to encounter problems if they try to limit it.

People want to be able to make interesting points and say clever things, but that requires being willing to look at things in a different way than convention, question assumptions, and so on, in a comprehensive way, and not just inside a tiny little box of stuff they’re comfortable thinking about. Limiting yourself to thinking about things within a tiny little box is an unphilosophical attitude. So basically people want some of the results of philosophy but they don’t want to be philosophers.

A: Maybe you could make an analogy with fitness. Lots of people make some effort to incorporate a bit of physical activity into their day. And it helps some - going for a walk while listening to an audiobook is better than nothing - but if they actually want to make a big physical transformation in what their body is like, they actually have to make a serious effort. And some people at least want the results of such a physical transformation, but they don’t actually want to be what is required to bring about that transformation. If they could take a pill to be big and strong, they’d do it, but they don’t want to spend a bunch of time exercising - they’d rather relax and watch TV.

So some common patterns of what happens are:

- People maybe get a bit more active, and it helps a bit, but it’s not enough activity, or not targeted or planned well enough, to make a big difference in their lives. There wasn’t any intent to get super serious, even from the beginning, and so they’re permanently stuck at a sort of hobbyist level.

- People have an initial intent to get very fit, but then they’re like “omg wow this is super hard and i’m sore and I just want to rest.” So they give up early.

There are of course people who make a big transformation in what their body is like, and I think that’s much more common for people doing fitness than people doing philosophy (cuz I see lots of fit people but not many good philosophers!). And lots of people are impressed by such successful super-fit people, but nonetheless stay stuck at wherever they are.

B: I think that’s a reasonable analogy. Let’s focus on the people who are initially ambitious. So people have some initial intent (to get super fit, to learn rational philosophy) because they like the idea they have of the end/result, but then they have trouble actually following through with the steps required. They encounter difficulty and give up. So, putting it abstractly, if you’re motivated by a particular end, but the ends seem really distant, and the means difficult, what are some possible strategies you could take to address that problem?

A: Hmm. Well, speaking abstractly, a couple of possibilities jump out at me. The first is to make smaller, more intermediate ends that are still motivating. The second is to learn how to enjoy/appreciate the means.

B: OK. I agree that those seem like reasonable approaches. So let’s take the example of fitness first. What would more intermediate ends look like?

A: Well, rather than the goal of “get super fit”, you might have a goal of “get through 10 push ups quickly”, or something like that. Or you might just aim to consistently have a certain amount of physical activity in the day - like that’s what the Move & Exercise rings are about on the Apple Watch. Or you might just notice and enjoy the fact that moving your arms or legs around seems a bit easier after doing some strength training - sometimes you can often “feel” that in a direct way after not a lot of time training.

B: And what would more intermediate ends look like in the context of philosophy?

A: Well, rather than “learn rational philosophy”, you might see if you can criticize anything using philosophical ideas within a single paragraph of a news article, or within a Tweet, or something like that. Or you might try to just spend a certain amount of time in a day reading and thinking about philosophy - like an hour. Or you might just reflect on how engaging with philosophy has recently helped in some way, like being calmer.

B: Okay. That sounds reasonable to me. Now let’s talk about appreciating the means in the context of fitness.

A: The means are exercising and learning about exercise. So you might learn to enjoy seeing what your body is capable of - like how many repetitions of some exercise you can do. Or you might learn to enjoy shrugging off minor pains and persisting in working out (shouldn’t ignore serious stuff, obviously, but I think that many people may give up early and unnecessarily). Or you might just reflect on the enjoyableness of your body in motion during running or cycling or lifting a heavy weight or whatever.

B: And how might you appreciate the means in the context of philosophy?

A: Hmm. Well I think the means there would be stuff like reading philosophy, having discussions about philosophy with wise people and “losing” debates, organizing ideas, and that kind of thing.

So you could try to learn to take pleasure in the act of reading philosophy or in the labor of organizing ideas (in the form of mindmaps or whatever) in order to understand philosophy. If it feels like tedious schoolwork, and not like something enjoyable that you would do for its own sake, then I think that is a sign that there is something wrong there and that there is room for improvement in this area. Unfortunately, I don’t have a lot of concrete steps here. I often greatly enjoy reading philosophy and that sort of thing when I actually spend time to do. I don’t think I have spent nearly as much time as I should have, but I don’t think this is where my big issue is.

Much trickier for me (and I think most people) is the right attitude to have to discussions. I think if you find someone wiser than you to talk to - which is something that will greatly aid your philosophical progress - then you have to expect to “lose” lots of discussion points and learn a lot. I think that this is something that I and many other people find very difficult in most contexts - particularly in a public context - because there is some perceived loss of face or loss of status or something in repeatedly “losing” discussions to someone. There may also be some feeling of guilt or foolishness in having strongly believed something and then coming to the view that one’s beliefs were not warranted. So I think this is an important thing to address. I think that if one does not find “losing” discussions to be a very enjoyable and important activity - as opposed to something painful - then one will be operating under a big handicap.

So one needs to learn to approach discussions differently. One approach might be to reframe “losing” a discussion as gaining knowledge, gaining humility, having an error corrected, etc.. What are you actually “losing” of importance, but ignorance and misconceptions? Another is to explicitly think about and appreciate the enormous value that having someone to point out your misconceptions represents. Imagine if such people didn’t exist - imagine if you were actually the smartest and wisest person in the world (ack!) - and you were left alone in the world, with nothing but your own mind and misconceptions and intellectual integrity to guide you to truth. That sort of “negative visualization” should help you be more appreciative of the existence of such people, or at least rob some of the sting from the social problem of having “lost” a discussion. Another approach might be to concretely think about the consequences of not having corrected the error. Like, what mistakes would you have been led into, and how many other people might have you persuaded of falsehood?