Chapter 1 Ten Principles of Economics

1-1 How People Make Decisions

There is no mystery about what an economy is. Whether it encompasses Los Angeles, the United States, or the entire planet, an economy is just a group of people dealing with one another as they go about their lives.

That seems like an odd definition. I don’t think they intend for it to be the primary definition of economics, but its the first one you’re offered. Are teams (groups) who play sports against each other considered economies here?

The first four principles below are concerned with individual decisions.

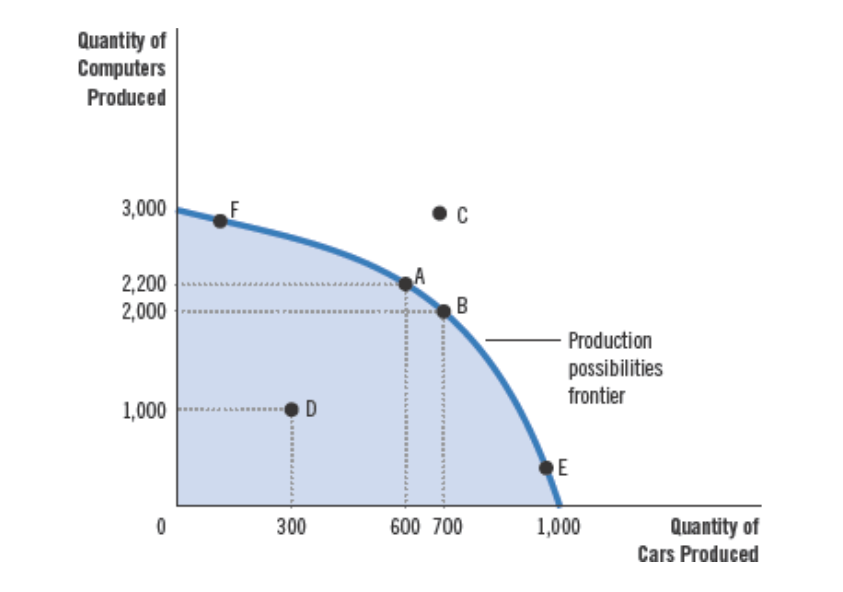

1-1a Principle 1: People Face Trade-Offs

Life has trade-offs. The time I’m spending reading this textbook right now could be used to read something else, play games, eat, nap, run, lift weights, etc. By choosing one thing you give up on the other things. The other things you gave up are the trade-offs for what you chose to do.

A common societal trade-off is between efficiency and equality.

Efficiency means that society is getting the greatest benefits from its scarce resources. Equality means that those benefits are distributed uniformly among society’s members. In other words, efficiency refers to the size of the economic pie, while equality refers to how evenly the pie is sliced.

1-1b Principle 2: The Cost of Something Is What You Give Up To Get It

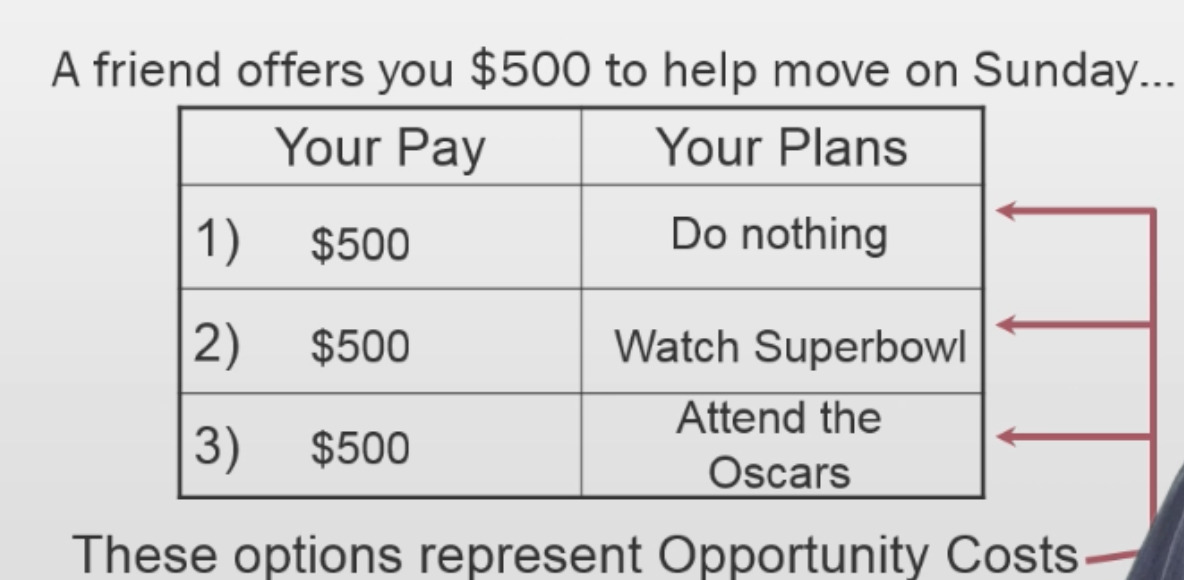

Opportunity Cost - “Whatever must be given up to obtain some item”

The cost of college is not just the cost of tuition, books, dorming, food, and gas. Its also the time you could be spending doing other things including activities that would make you money.

Hmm. I guess opportunity costs focus on realistic options? I think there are nearly infinitely many things you’re giving up by choosing something. I order food from my local chinese place. The opportunity cost would technically be every restaurant (and all the other things I could do with the money). Right? That’s so vast. I think this is more meant to focus on realistic options? So the “actual” opportunity cost would be reasonably close restaurants that you like eating at.

1-1c Principle 3: Rational People Think at the Margin

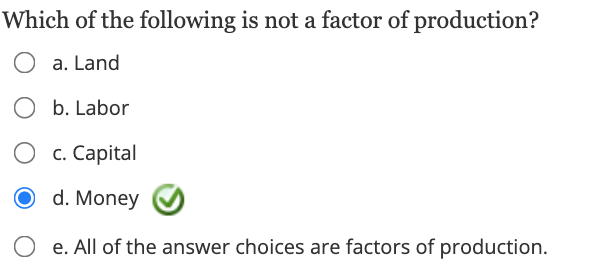

Economics assume rational individuals.

Rational People - “people who systematically and purposefully do the best they can to achieve their objectives”

You don’t (usually) decide between not eating all day and eating all day, or not studying all day and studying all day. You’re more likely to make smaller decisions such as studying for an extra hour, eating just a little bit more cake, etc.

Economists use the term marginal change to describe an incremental adjustment to an existing plan of action.

Lets say you pay $30 a month for a streaming service with unlimited movies. The marginal cost of watching another movie is $0. It doesn’t cost you anything (at least not cash wise) to watch another movie.

1-1d Principle 4: People Respond to Incentives

An incentive is something that gets people to act. It can either be rewards or punishments.

One economist went so far as to say that the entire field could be summarized as simply, “People respond to incentives. The rest is commentary.”

1-2 How People Interact

The next three principles will deal with interactions between individuals.

1-2a Principle 5: Trade Can Make Everyone Better Off

Trade between two countries can make each country better off. Even when trade in the world economy is competitive, it can lead to a win–win outcome for the countries involved.

Countries that compete still benefit from trade between each other.

Trade allows for specialization.

1-2b Principle 6: Markets Are Usually a Good Way to Organize Economic Activity

In a market economy the decisions of a central planner are replaced by those of millions of firms and households. Firms decide whom to hire and what to make. Households decide where to work and what to buy with their incomes.

As you study economics, you will learn that prices are the instrument with which the invisible hand directs economic activity.

This makes prices sound very important. That makes sense. I remember hearing about Von Mises debunking planned economies because they can’t price correctly or something.

1-2c Principle 7: Governments Can Sometimes Improve Market Outcomes

Most importantly, market economies need institutions to enforce property rights so individuals can own and control scarce resources.

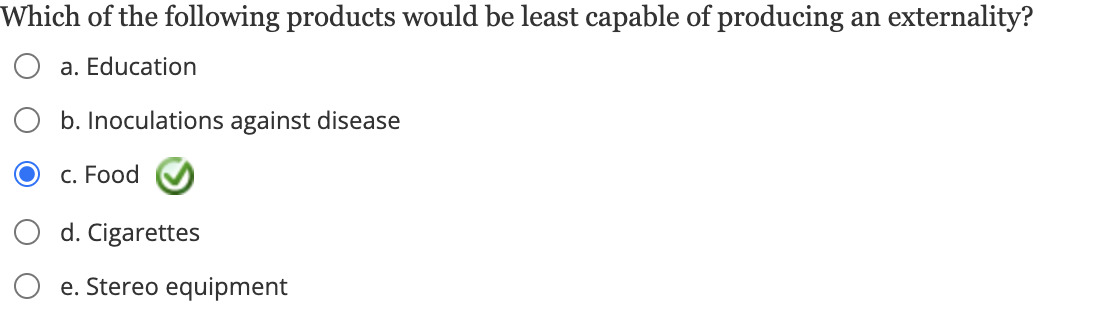

Economists use the term market failure to refer to a situation in which the market does not produce an efficient allocation of resources on its own. One possible cause of market failure is an externality, which is the impact of one person’s actions on the well-being of a bystander. The classic example of an externality is pollution.

Hmm. So their saying its a failure of the market to calculate the costs of what you’re doing to other people? Mmm. I can see that. I can see how this is a “failure” of the market. WIthout the government getting involved I can believe many businesses would just harm people through pollution and not take the costs of what they’re doing into account.

Another market “failure” are monopolies.

The above are things the government can address to make the economy more efficient. The government can also address things to make the economy more equal.

1.3 How the Economy as a Whole Works

First part covered individuals, second part covered interactions between individuals, third part will cover the whole economy now.

1.3a Principle 8: A Country’s Standard of Living Depends on Its Ability to Produce Goods and Services

People/countries with higher average incomes have better qualities of life. From access to food, medicine, technology, etc.

Almost all variation in living standards is attributable to differences in countries’ productivity—that is, the amount of goods and services produced by each unit of labor input.

The relationship between productivity and living standards is simple, but its implications are far-reaching. If productivity is the main determinant of living standards, other explanations must be less important.

1.3b Principle 9: Prices Rise When the Government Prints Too Much Money

In January 1921, a daily newspaper in Germany cost 0.30 marks. Less than two years later, in November 1922, the same newspaper cost 70,000,000 marks. All other prices in the economy rose by similar amounts. This episode is one of history’s most spectacular examples of inflation, an increase in the overall level of prices in the economy.

What causes inflation? In almost all cases of large or persistent inflation, the culprit is growth in the quantity of money. When a government creates large quantities of the nation’s money, the value of the money falls.

1.3c Principle 10: Society Faces a Short-Run Trade-Off between Inflation and Unemployment

Most economists describe the short-run effects of money growth as follows:

Increasing the amount of money in the economy stimulates the overall level of spending and thus the demand for goods and services.

Higher demand will, over time, cause firms to raise their prices, but in the meantime, it encourages them to hire more workers and produce a larger quantity of goods and services.

More hiring means lower unemployment.

So in the short-term people get hired. Long-term prices go up.

1.4 Conclusion

How People Make Decisions

- People face trade-offs.

- The cost of something is what you give up to get it.

- Rational people think at the margin.

- People respond to incentives.

How People Interact

- Trade can make everyone better off.

- Markets are usually a good way to organize economic activity.

- Governments can sometimes improve market outcomes.

How the Economy as a Whole Works

- A country’s standard of living depends on its ability to produce goods and services.

- Prices rise when the government prints too much money.

- Society faces a short-run trade-off between inflation and unemployment.