I was talking with someone about people not being very good at math and logic and that being relevant to philosophy errors. Also from the conversation they brought up the book Governed By Affect by Michael Pettit. I found something potentially relevant there: a logic error by Pettit. Here’s the first paragraph I read (from early in chapter 5; I saw something familiar in the table of contents and skipped to it):

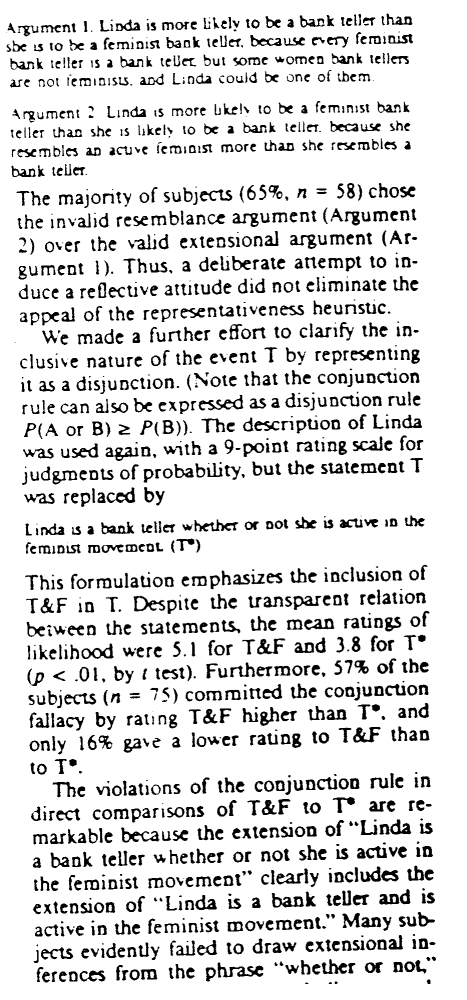

The famous Linda Problem, first introduced in 1983, exemplified Kahneman and Taversky’s approach to understanding the fallacies of human judgments when the mind largely runs on automatic. They presented participants with the following description of a fictional person: “Linda is 31 years old, single, outspoken and very bright. She majored in philosophy. As a student, she was deeply concerned with issues of discrimination and social justice, and also participated in antinuclear demonstrations.” They then asked participants to rank a variety of statements about Linda in the order of their likelihood. Respondents tended to rank the conjunction of attributes “Linda is a bank teller and is active in the feminist movement” as more likely than either attribute appearing in isolation. The conjoined statement appeared to be more representative of her person as a whole, even though statistically speaking, she more likely possessed only one of the attributes.[4] People failed at reasoning by succumbing to quick, appeasing, intuitive shortcuts instead of slowing their thinking sufficiently to contemplate the problem to solve it correctly. [bold added]

Here, Pettit is talking about laypeople being bad at logic. But he made his own mistakes.

Pettit compared having both attributes to possessing “only one” of the attributes. That’s not the correct comparison. He’s comparing

- bank teller and feminist (this is the conjunction they’re talking about because it uses “and” to conjoin two attributes)

to

- bank teller and not feminist (wrong)

rather than comparing to

- bank teller and may or may not be feminist (right)

which was originally presented as

- bank teller (means the same thing as 3)

In the correct comparison, the conjunction option (1) is strictly worse (3 is higher probability than 1). The argument is that, since people prefer a strictly worse thing, they must be irrational, biased, or something else bad.

In Pettit’s version, he says having “only” one trait is more likely than having both. But that depends. X&Y can be more likely than X&!Y. By saying “only” one specific thing, in the context of two things, he’s actually comparing two conjunctions. Statement 2 is both an inaccurate description of the research and also not higher probability than statement 1 as Pettit claims.

Here is the original paper for the Linda problem:

They even tried wording it as “Linda is a bank teller whether or not she is active in the feminist movement” and people still thought that was less likely than “Linda is a bank teller and is active in the feminist movement”. Despite this, Pettit somehow thought the alternative was that Linda was only a bank teller (not a feminist), and then he incorrectly judged the comparative probability for that.

The original research involved multiple additional efforts to clarify this (to study participants, not directly to people reading the paper like Pettit). I wonder if Pettit read the paper while he was writing the book, years earlier, or never. But you can’t explain this as just bad research methods and bad memory. Even setting aside Pettit’s incorrect statement about what the original research said, he also made his own incorrect statement about probability. His logic/math error is visible without reading the original paper.

Pettit continues:

Such simple demonstrations of people’s incapacity to reason properly galvinized a wide of range of psychologists by offering them an exciting means of intervening in the most pressing issues of the day. Gone was the layperson functioning as a deliberative chess expert carefully testing hypotheses about the world.[5]

I don’t like it when experts like Pettit talk about the incapacity of laypeople while making their own similar errors. Maybe you shouldn’t ever be condescending, but you at the very least shouldn’t be condescending if you can’t do a lot better than the people you’re disrespecting.

I’m not trying to single out Pettit as worse than his peers. For me, quickly finding pretty basic errors is just a typical experience when reading books and papers by experts. I think it’s a widespread problem.