Continuing reading chapter 18.

As well as writing my thoughts this time, I’m also going to try writing summary notes about each passage I comment on.

Note I have skipped some passages, I’ve focused on the passages that I think are most central to the point or that I have other comments on.

I think we can describe Utopianism as a result of a form of rationalism, and I shall try to show that this is a form of rationalism very different from the form in which I and many others believe. So I shall try to show that there exist at least two forms of rationalism, one of which I believe is right and the other wrong; and that the wrong kind of rationalism is the one which leads to Utopianism.

Summary:

There are at least two forms of rationalism. The wrong form of rationalism leads to utopianism.

Thoughts:

I guess this is roughly the divide between Critical Rationalism and Rationalism. Or possibly just one distinguishing feature between Critical Rationalism and other forms of Rationalism.

An action, it may be argued, is rational if it makes the best use of the available means in order to achieve a certain end. The end, admittedly, may be incapable of being determined rationally. However this may be, we can judge an action rationally, and describe it as rational or adequate, only relative to some given end. Only if we have an end in mind, and only relative to such an end, can we say that we are acting rationally.

Summary:

For an action to be rational it must have an end and make best use of the means to achieve that end.

Thoughts:

I agree with this. I think without an end there is no way of measuring what the correct course of action to reach it. I think people generally (possibly always) have some sort of end to their actions, but they don’t often recognise it or lie about what it is. A lot of people lie and say their actions have no point, I think these people have some sort of end supplied by intuition (such a “fun”). Sometimes people pretend to not have a purpose (serving another end - social signalling by some standard of being “edgy” or “fun”).

In the [case of political action for improving some law of the state it] will be rational only if we first determine the final ends of the political changes which we intend to bring about. It will be rational only relative to certain ideas of what a state ought to be like. Thus it appears that as a preliminary to any rational political action we must first attempt to become as clear as possible about our ultimate political ends; for example the kind of state which we should consider the best; and only afterwards can we begin to determine the means which may best help us to realize this state, or to move slowly towards it, taking it as the aim of a historical process which we may to some extent influence and steer towards the goal selected.

Summary:

So for political action intended to improve the state to be rational, it must have an end in mind.

Thoughts:

I think this makes sense too. I’m including this as I think it’s a main point of the section I’m reading.

Now it is precisely this view which I call Utopianism. Any rational and nonselfish political action, on this view, must be preceded by a determination of our ultimate ends, not merely of intermediate or partial aims which are only steps towards our ultimate end, and which therefore should be considered as means rather than as ends; therefore rational political action must be based upon a more or less clear and detailed description or blueprint of our ideal state, and also upon a plan or blueprint of the historical path that leads towards this goal.

Summary:

A rational and nonselfish political action requires a blueprint of an ideal state and the path leading to that goal. This is Utopianism.

Thoughts:

I don’t think I agree with this. I think these is some unstated additional premise behind Utopianism beyond what has been said so far. I think the premise is something about assuming infallibility - that a plan, once set, must be unwaveringly followed.

(Note Popper does go on to reveal this premise a bit later which I get to later in this post.)

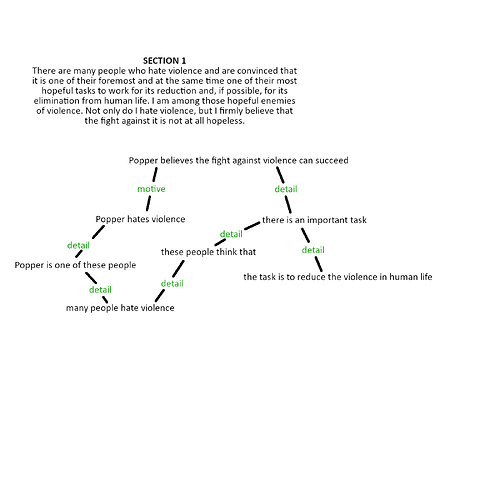

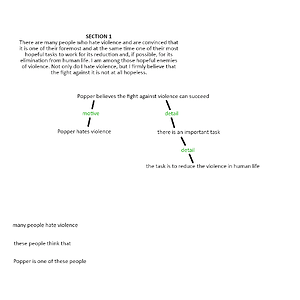

That [Utopianism] is self-defeating is connected with the fact that it is impossible to determine ends scientifically. There is no scientific way of choosing between two ends. Some people, for example, love and venerate violence. For them a life without violence would be shallow and trivial. Many others, of whom I am one, hate violence. This is a quarrel about ends. It cannot be decided by science. This does not mean that the attempt to argue against violence is necessarily a waste of time. It only means that you may not be able to argue with the admirer of violence. He has a way of answering an argument with a bullet if he is not kept under control by the threat of counter-violence. If he is willing to listen to your arguments without shooting you, then he is at least infected by rationalism, and you may, perhaps, win him over. This is why arguing is no waste of time–as long as people listen to you. But you cannot, by means of argument, make people listen to argument; you cannot, by means of argument, convert those who suspect all argument, and who prefer violent decisions to rational decisions. You cannot prove to them that they are wrong. And this is only a particular case, which can be generalized. No decision about aims can be established by purely rational or scientific means. Nevertheless argument may prove extremely helpful in reaching a decision about aims.

Summary:

There is no scientific way of choosing between two ends.

Some people like violence.

It’s impossible to argue with people who use violence in response.

Argument may help reach decisions about ends.

Thoughts:

I’m a little confused by this paragraph.

I’m not sure about ends not being reachable scientifically. I’m guessing the idea behind this is: the reason you can’t determine ends scientifically is that you can’t measure the result until you have the result.

I’m also not sure why the fact that some people like violence is related. Guessing again, I think this means something like: there are pro-violence people in the state (or at least, you can’t guarantee there aren’t) so making a decision that requires all of the state to be involved is rationally impossible as some members may oppose it violently.

That the Utopian method, which chooses an ideal state of society as the aim which all our political actions should serve, is likely to produce violence can be shown thus. Since we cannot determine the ultimate ends of political actions scientifically, or by purely rational methods, differences of opinion concerning what the ideal state should be like cannot always be smoothed out by the method of argument. They will at least partly have the character of religious differences. And there can be no tolerance between these different Utopian religions. Utopian aims are designed to serve as a basis for rational political action and discussion, and such action appears to be possible only if the aim is definitely decided upon. Thus the Utopianist must win over, or else crush, his Utopianist competitors who do not share his own Utopian aims, and who do not profess his own Utopianist religion.

Summary:

A state can only be aimed at one Utopian blueprint.

Competing Utopianists with different blueprints must be convinced or crushed.

Thoughts:

So from the Utopianist perspective, there is only one correct form for society. Others with competing views must be convinced or coerced into conforming with the one view.

A hypothetical integrating with some previous passages:

A politician wants to take rational political action. They have a specific vision for society and want to implement it. They try to make changes towards their vision. Some people in the state disagree with the changes and can not be convinced. The politician then must force dissenters to comply to pursue their Utopian vision.

I think this is roughly what Popper is saying, but I don’t think I agree that it’s accurate. A politician in that situation could continue trying to convince people of their Utopian vision. Though I think it would be very very hard to convince every member of the state to agree with it and keep agreeing with it. I think maybe there is another unstated premise about Utopianism in this chapter, something about it being urgent to proceed? Maybe something like: A Utopianist sees society is bad and it must be changed and it’s harmful not to change it?

The use of violent methods for the suppression of competing aims becomes even more urgent if we consider that the period of Utopian construction is liable to be one of social change. In such a time ideas are liable to change also. Thus what may have appeared to many as desirable at the time when the Utopian blueprint was decided upon may appear less desirable at a later date. If this is so, the whole approach is in danger of breaking down. For if we change our ultimate political aims while attempting to move towards them we may soon discover that we are moving in circles. The whole method of first establishing an ultimate political aim and then preparing to move towards it must be futile if the aim may be changed during the process of its realization. It may easily turn out that the steps so far taken lead in fact away from the new aim. And if we then change direction in accordance with our new aim we expose ourselves to the same risk. In spite of all the sacrifices which we may have made in order to make sure that we are acting rationally, we may get exactly nowhere–although not exactly to that ‘nowhere’ which is meant by the word ‘Utopia’.

Summary:

Utopian construction takes time. Things might go wrong or things might change so progress is slowed or even reversed.

It may become apparent that the Utopian vision is flawed, changing to a new Utopian vision will only being the same process again and potentially run into similar problems.

Thoughts:

I think this reveals another premise between Popper’s idea of Utopianism. Something about scale, it must necessarily have a certain amount of changes which will result in it taking a substantial amount of time to create.

I do think this is a reasonable interpretation of “Utopian”. I don’t think someone who says “if we change this one thing which is quick and easy and harmless we’ll be living in a Utopia!” could reasonably be called a Utopianist, even if that would make society flawless by their standards. In normal conversation if someone mentioned Utopian thinking I would have assumed it would include large scale changes. I didn’t in this case as Popper was building from a specific premise (a kind of Rationalism) so I didn’t want to assume.

If I were to give a simple formula or recipe for distinguishing between what I consider to be admissible plans for social reform and inadmissible Utopian blueprints, I might say:

Work for the elimination of concrete evils rather than for the realization of abstract goods. Do not aim at establishing happiness by political means. Rather aim at the elimination of concrete miseries. Or, in more practical terms: fight for the elimination of poverty by direct means–for example, by making sure that everybody has a minimum income. Or fight against epidemics and disease by erecting hospitals and schools of medicine. Fight illiteracy as you fight criminality. But do all this by direct means. Choose what you consider the most urgent evil of the society in which you live, and try patiently to convince people that we can get rid of it.

Summary:

To distinguish between admissible social reform and inadmissible Utopian blueprints: Aim at elimination of concrete miseries, rather than establishing happiness by political means.

My thoughts:

I think this is in principle a good way to approach political change.

So, my understanding of Utopianism as Popper describes it, including my guesses at unstated premises:

- Based in Rationalism.

- Includes sweeping, large-scale changes across the state.

- Must be done urgently, to the point of coercing dissenters.

I guess I still consider that “Must be done urgently” is not fundamentally part of Utopianism. I think a very patient Utopianist who wants to convince everyone to join in, including convincing everyone who changes their mind during the process, is theoretically possible. But when it comes to effective political action, I don’t think such a person could realistically every achieve anything except maybe in a very small group of people.

So the comparison between admissible social reform and inadmissible social reform is between effective political actions.

This section on Utopianism ultimately argues taking an incremental approach in politics (solve some solid misery today, rather than constructing an elaborate plan that will solve everyone’s miseries eventually). It claims that Utopianism requires violence and will be highly error-prone which will require more violence (and I agree that attempting a Utopian vision in any sort of useful timeframe does require violence).

Conclusion:

Political action should be taken incrementally to tackle individual concrete issues, rather than planning complex sweeping changes to solve everything.

There are a few more pages to the chapter which do add more to this and I will explore more another time, but I think this covers the central point of the chapter so I wanted to cover these passages at once.