Yes, I am still confused. I’m not sure how to determine whether there is a cause and effect relationship with this sentence. I read that a cause is something that is both necessary and sufficient for the effect. I found a legal definition of a cause:

legal cause | Wex | US Law | LII / Legal Information Institute (cornell.edu)

A cause that produces a result in a natural and probable sequence and without which the result would not have occurred.

That definition seems to include the necessary component but not the sufficient component of being a cause.

Looking at the sentence again:

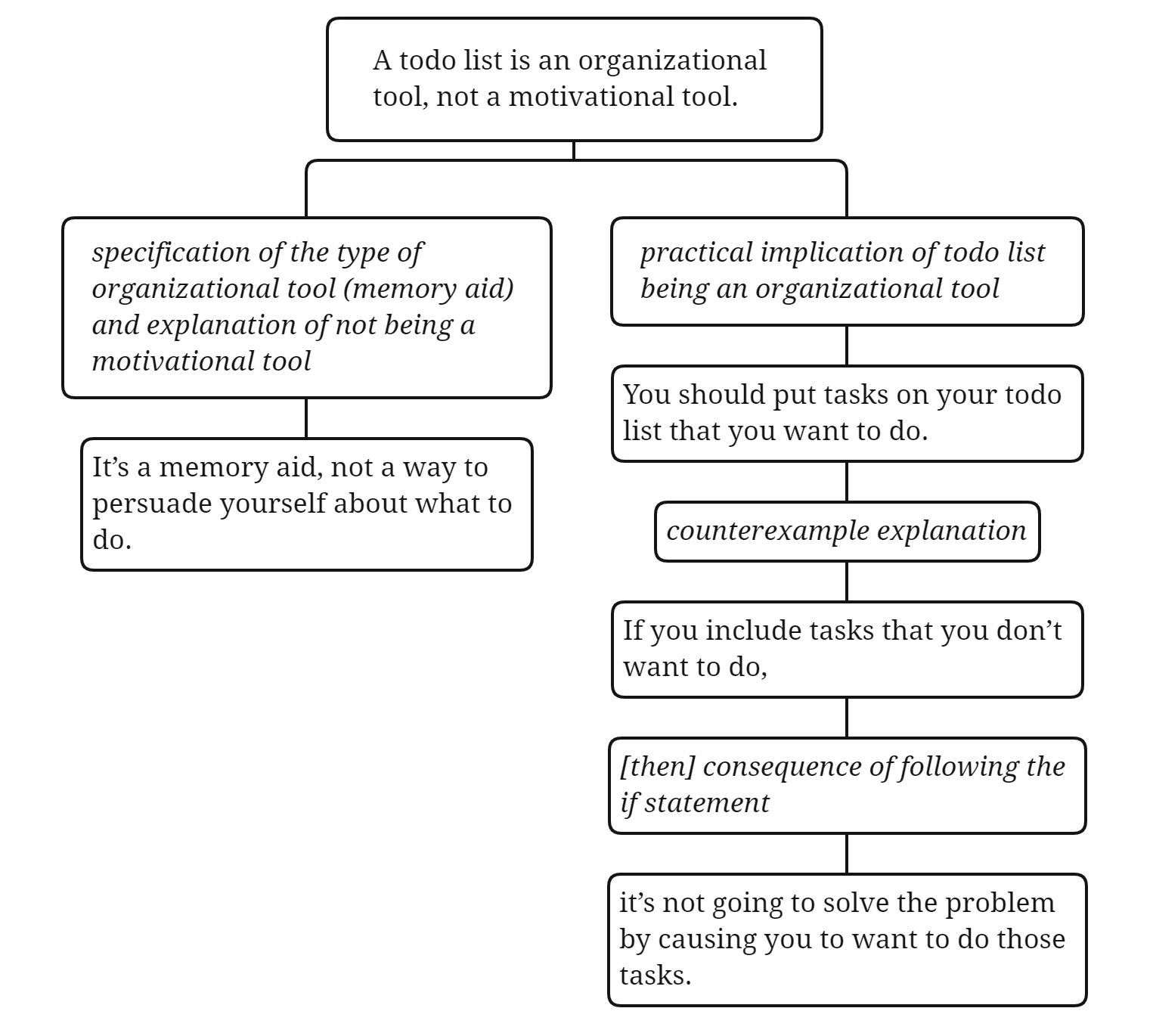

If you include tasks that you don’t want to do, it’s not going to solve the problem by causing you to want to do those tasks.

Rewrite adding my interpolations:

If you include tasks that you don’t want to do, [then the inclusion of those tasks is] not going to solve the problem [of doing the tasks on your todo list] by causing you to want to do those tasks.

Is including tasks that you don’t want to do necessary for not solving the problem in qualified manner above? No, there are other ways to make it so you are not going to solve the problem of doing the tasks by causing yourself to want to do the task.

Is including tasks that you don’t want to do suffficient for not solving the problem in qualified manner above? Idk. Is putting the tasks on your todo list that you don’t want to do enough to prevent you from solving the problem? No, I think you could still find a way to want to do the tasks on your todo list or a way to not want them on the list. But you won’t have solved the problem by having the unwanted items on the list. Something else would have to happen, like some kind of creative problem solving.

I’m still very unsure even after attempting some further thought and analysis. But overall, the sentence looks likes it says that there is not a causal relationship between adding unwanted items to the todo list and wanting to do those items.

Maybe that stuff above, about necessary vs sufficient, isn’t even relevant to my confusion or might be adding to it. My confusion might just have to do with making sense of the clauses’ meanings. The second clause is based on the linking verb “is”. That indicates the clause is depicting an equivalence or state of being relationship. I read “it” as meaning “the inclusion of tasks that you don’t want to do on your todo list”.The verb “is” has modifier “not”. So, you have a non-equivalence or non-state-of-being relationship. Maybe I should be looking at “not” a part of the “then” statement instead of as a part of the sentence level if/then logic. So, the overall sentence logic is just “If X, Then Y” instead of “If X, Then not Y”. The sentence meaning would be if you do X, then you will end up with the overall situation Y. In that case X causes Y.