Im gonna post what I’ve read here and try to practice things related to the reading(e.g. definitions/grammar/prarphrase/analysis).

What I read

“You don’t have to help. You don’t have to feel anything for any of us.”

Rearden had never known what his brother was doing or wished to do. He had sent Philip through

college, but Philip had not been able to decide on any specific ambition. There was something wrong, by

Rearden’s standards, with a man who did not seek any gainful employment, but he would not impose his

standards on Philip; he could afford to support his brother and never notice the expense. Let him take it

easy, Rearden had thought for years, let him have a chance to choose his career without the strain of

struggling for a livelihood.

“What were you doing today, Phil?” he asked patiently.

“It wouldn’t interest you.”

“It does interest me. That’s why I’m asking.”

“I had to see twenty different people all over the place, from here to Redding to Wilmington.”

“What did you have to see them about?”

“I am trying to raise money for Friends of Global Progress.”

Rearden had never been able to keep track of the many organizations to which Philip belonged, nor to

get a clear idea of their activities. He had heard Philip talking vaguely about this one for the last six

months.

It seemed to be devoted to some sort of free lectures on psychology, folk music and co-operative

farming. Rearden felt contempt for groups of that kind and saw no reason for a closer inquiry into their

nature.

He remained silent. Philip added without being prompted, “We need ten thousand dollars for a vital

program, but it’s a martyr’s task, trying to raise money. There’s not a speck of social conscience left in people. When I think of the kind of bloated money-bags I saw today—why, they spend more than that on any whim, but I couldn’t squeeze just a hundred bucks a piece out of them, which was all I asked. They have no sense of moral duty, no . . . What are you laughing at?” he asked sharply. Rearden stood before him, grinning.

It was so childishly blatant, thought Rearden, so helplessly crude: the hint and the insult, offered together.

It would be so easy to squash Philip by returning the insult, he thought—by returning an insult which

would be deadly because it would be true—that he could not bring himself to utter it. Surely, he thought,

the poor fool knows he’s at my mercy, knows he’s opened himself to be hurt, so I don’t have to do it,

and my not doing it is my best answer, which he won’t be able to miss.

What sort of misery does he really live in, to get himself twisted quite so badly?

And then Rearden thought suddenly that he could break through Philip’s chronic wretchedness for once,

give him a shock of pleasure, the unexpected gratification of a hopeless desire. He thought: What do I care about the nature of his desire?—it’s his, just as Rearden Metal was mine—it must mean to him what that meant to me—let’s see him happy just once, it might teach him something—didn’t I say that

happiness is the agent of purification?—I’m celebrating tonight, so let him share in it—it will be so much for him, and so little for me.

“Philip,” he said, smiling, “call Miss Ives at my office tomorrow.

She’ll have a check for you for ten thousand dollars.”

Philip stared at him blankly; it was neither shock nor pleasure; it was just the empty stare of eyes that

looked glassy.

“Oh,” said Philip, then added, “We’ll appreciate it very much.”

There was no emotion in his voice, not even the simple one of greed.

Rearden could not understand his own feeling: it was as if something leaden and empty were collapsing

within him, he felt both the weight and the emptiness, together. He knew it was disappointment, but he wondered why it was so gray and ugly.

“It’s very nice of you, Henry,” Philip said dryly. “I’m surprised. I didn’t expect it of you.”

“Don’t you understand it, Phil?” said Lillian, her voice peculiarly clear and lilting. “Henry’s poured his

metal today.” She turned to Rearden. “Shall we declare it a national holiday, darling?”

“You’re a good man, Henry,” said his mother, and added, “but not often enough.”

Rearden stood looking at Philip, as if waiting.

Philip looked away, then raised his eyes and held Rearden’s glance, as if engaged in a scrutiny of his

own.

I want to know what crude means here(my bold added):

It was so childishly blatant, thought Rearden, so helplessly crude: the hint and the insult, offered together.

It would be so easy to squash Philip by returning the insult, he thought—by returning an insult which

would be deadly because it would be true—that he could not bring himself to utter it.

What I found on the internet:

Merriam Webster:

marked by the primitive, gross, or elemental or by uncultivated simplicity or vulgarity

Ox languages:

constructed in a rudimentary or makeshift way.

I think both definitions fit, but idk which one is best.

I think I get the second definition the most.

This is actually hard to practice. Why?

- Hard to confirm if the definition applies to the book’s word

- Hard to think of things that are crude

- Hard to put into other words why something is crude

Here is the quote where the “hint” and “insult” are from:

He remained silent. Philip added without being prompted, “We need ten thousand dollars for a vital

program, but it’s a martyr’s task, trying to raise money. There’s not a speck of social conscience left in people. When I think of the kind of bloated money-bags I saw today—why, they spend more than that on any whim, but I couldn’t squeeze just a hundred bucks a piece out of them, which was all I asked. They have no sense of moral duty, no . . . What are you laughing at?” he asked sharply. Rearden stood before him, grinning.

My best guess is that Rearden sees Phillip’s dialogue as trying to be an insult to Reardan cuz Rearden is rich. Phillip is also trying to hint to Rearden that he’s asking him for money but is doing it in an indirect way.

Im gonna try to use crude in a few sentences:

- Tying rope around me and my car seat is a crude way of using a seatbelt

- Not learning philosophy and becoming smarter is a crude way of living life to its fullest.

- It’s crude to use a shirt as a blanket.

It’s hard to think of anymore.

What I reas from Ch.3 of Part 1

“Material greed isn’t everything. There are non-material ideals to consider.” “I confess to a feeling of shame when I think that we own a huge network of railways, while the Mexican people have nothing but one or two inadequate lines.” “The old theory of economic self-sufficiency has been exploded long ago. It is impossible for one country to prosper in the midst of a starving world.”

She thought that to make Taggart Transcontinental what it had been once, long before her time, every available rail, spike and dollar was needed—and how desperately little of it was available.

They spoke also, at the same session, in the same speeches, about the efficiency of the Mexican government that held complete control of everything. Mexico had a great future, they said, and would become a dangerous competitor in a few years. “Mexico’s got discipline,” the men of the Board kept saying, with a note of envy in their voices.

James Taggart let it be understood—in unfinished sentences and undefined hints—that his friends in Washington, whom he never named, wished to see a railroad line built in Mexico, that such a line would be of great help in matters of international diplomacy, that the good will of the public opinion of the world would more than repay Taggart Transcontinental for its investment.

They voted to build the San Sebastián Line at a cost of thirty million dollars.

When Dagny left the Board room and walked through the clean, cold air of the streets, she heard two words repeated clearly, insistently in the numbed emptiness of her mind: Get out . . . Get out . . . Get out.

She listened, aghast. The thought of leaving Taggart Transcontinental did not belong among the things she could hold as conceivable. She felt terror, not at the thought, but at the question of what had made her think it. She shook her head angrily; she told herself that Taggart Transcontinental would now need her more than ever.

Two of the Directors resigned; so did the Vice-President in Charge of Operation. He was replaced by a friend of James Taggart.

Steel rail was laid across the Mexican desert—while orders were issued to reduce the speed of trains on the Rio Norte Line, because the track was shot. A depot of reinforced concrete, with marble columns and mirrors, was built amidst the dust of an unpaved square in a Mexican village—while a train of tank cars carrying oil went hurtling down an embankment and into a blazing junk pile, because a rail had split on the Rio Norte Line. Ellis Wyatt did not wait for the court to decide whether the accident was an act of God, as James Taggart claimed. He transferred the shipping of his oil to the Phoenix-Durango, an obscure railroad which was small and struggling, but struggling well. This was the rocket that sent the Phoenix-Durango on its way. From then on, it grew, as Wyatt Oil grew, as factories grew in nearby valleys—as a band of rails and ties grew, at the rate of two miles a month, across the scraggly fields of Mexican corn.

Dagny was thirty-two years old, when she told James Taggart that she would resign. She had run the Operating Department for the past three years, without title, credit or authority. She was defeated by loathing for the hours, the days, the nights she had to waste circumventing the interference of Jim’s friend who bore the title of Vice-President in Charge of Operation. The man had no policy, and any decision he made was always hers, but he made it only after he had made every effort to make it impossible. What she delivered to her brother was an ultimatum. He gasped, “But, Dagny, you’re a woman! A woman as Operating Vice-President? It’s unheard of! The Board won’t consider it!”

“Then I’m through,” she answered.

She did not think of what she would do with the rest of her life. To face leaving Taggart Transcontinental was like waiting to have her legs amputated; she thought she would let it happen, then take up the load of whatever was left.

She never understood why the Board of Directors voted unanimously to make her Vice-President in Charge of Operation.

It was she who finally gave them their San Sebastián Line. When she took over, the construction had been under way for three years; one third of its track was laid; the cost to date was beyond the authorized total. She fired Jim’s friends and found a contractor who completed the job in one year.

The San Sebastián Line was now in operation. No surge of trade had come across the border, nor any trains loaded with copper. A few carloads came clattering down the mountains from San Sebastián, at long intervals. The mines, said Francisco d’Anconia, were still in the process of development. The drain on Taggart Transcontinental had not stopped.

Now she sat at the desk in her office, as she had sat for many evenings, trying to work out the problem of what branches could save the system and in how many years.

The Rio Norte Line, when rebuilt, would redeem the rest. As she looked at the sheets of figures announcing losses and more losses, she did not think of the long, senseless agony of the Mexican venture. She thought of a telephone call. “Hank, can you save us? Can you give us rail on the shortest notice and the longest credit possible?” A quiet, steady voice had answered, “Sure.”

The thought was a point of support. She leaned over the sheets of paper on her desk, finding it suddenly easier to concentrate. There was one thing, at least, that could be counted upon not to crumble when needed.

James Taggart crossed the anteroom of Dagny’s office, still holding the kind of confidence he had felt among his companions at the barroom half an hour ago. When he opened her door, the confidence vanished. He crossed the room to her desk like a child being dragged to punishment, storing the resentment for all his future years.

I’m gonna practice finding the verb in some paragraphs. Maybe finding the verb quicker will help paint a better picture of what is happening in the story.

I’ll do step one of finding the verb from the FI grammar article:

Step 1 – Verb

The verb is the most important part of a simple sentence because it tells us what’s happening in the sentence. There are two types: action verbs and linking verbs. The verb determines which of the two sentence types you’re dealing with (action sentence or linking sentence).

The first step for analyzing a sentence is finding the verb. The verbs in the examples are “threw” and “is”.

My bolds are what I think the verbs are(italic bolds are verbs too but I’m not certain about it):

She thought that to make Taggart Transcontinental what it had been once, long before her time, every available rail, spike and dollar was needed—and how desperately little of it was available.

James Taggart let it be understood—in unfinished sentences and undefined hints—that his friends in Washington, whom he never named, wished to see a railroad line built in Mexico, that such a line would be of great help in matters of international diplomacy, that the good will of the public opinion of the world would more than repay Taggart Transcontinental for its investment.

They voted to build the San Sebastián Line at a cost of thirty million dollars.

She listened, aghast. The thought of leaving Taggart Transcontinental did not belong among the things she could hold as conceivable. She felt terror, not at the thought, but at the question of what had made her think it. She shook her head angrily; she told herself that Taggart Transcontinental would now need her more than ever.

Two of the Directors resigned; so did the Vice-President in Charge of Operation. He was replaced by a friend of James Taggart.

Steel rail was laid across the Mexican desert—while orders were issued to reduce the speed of trains on the Rio Norte Line, because the track was shot. A depot of reinforced concrete, with marble columns and mirrors, was built amidst the dust of an unpaved square in a Mexican village—while a train of tank cars carrying oil went hurtling down an embankment and into a blazing junk pile, because a rail had split on the Rio Norte Line. Ellis Wyatt did not wait for the court to decide whether the accident was an act of God, as James Taggart claimed. He transferred the shipping of his oil to the Phoenix-Durango, an obscure railroad which was small and struggling, but struggling well. This was the rocket that sent the Phoenix-Durango on its way. From then on, it grew, as Wyatt Oil grew, as factories grew in nearby valleys—as a band of rails and ties grew, at the rate of two miles a month, across the scraggly fields of Mexican corn.

I think next time I’ll just do simple sentences. Also maybe next time I could put a [ ] around the verb to make it more obvious what I marked.

Seems like you just used the first definitions offered on the websites you mentioned. Maybe try looking at lower(?) definitions? Here’s one from Merriam-Webster that I think works here:

lacking a covering, glossing, or concealing element : obvious

its the 4th definition.

So did finding the verbs help?

Oh yeah, I think I did.

Yeah, I’ll try that next time. Usually I skim the lower definitions. I don’t know why though.

Oh ok I could see how that definition works intuitively. The way Phillip is talking about rich people, how they’re floating money bags to him. He talks about it in an open manner. Like he’s not ashamed.

I actually don’t know. I thought maybe there is a bigger message that I can see if I work on verbs more.

I read from the beginning of chapter 4 for 9 pages in my physical book.

I tried to consciously focus finding the verbs while I read. I did that instead of focusing on the story more.

Whenever I would see an auxiliary verb like could, might, would, and must, I counted those as the verb. Im not sure about “had” as the verb. An example of “had” from the book:

She had not seen him for years.

That was when Dagny was talking about Francisco.

I know it sounds kind of obvious, but I noticed finding the verb shows something happening in the story. Like ‘Dagny walked on the street’ or ‘Dagny listened to music’. The amount of things that happen just add up and it’s a lot. It’s no wonder why sometimes I lose track of what’s happening in the story.

I think that’s a good observation, it gives you some intuition of what verbs are conceptually.

One thing you can do with finding verbs is divide them into two categories. Basically the boring and interesting verbs.

There are some common verbs that don’t have a lot of meaning on their own like do, have, is, am, are, was, were, could, should, would. I’d also add verbs for talking or thinking, like said, told, think.

For these more boring verbs, usually the key information in the sentence is found in other words.

Then all other verbs are the ones that stand out more, are less common, and can highlight something interesting happening. Many of these verbs are actions like sing, dance, hike, cook, study.

In “John is ugly.” the most interesting word is “ugly”. In “John cooked dinner.” the most interesting word is “cooked”.

Ok I’ll try that by writing it down next time

I’m going to practice finding just the boring verbs in some paragraphs of ch. 3. Square brackets mean I’m sure and curly brackets mean im unsure. Also the bolds are mine:

Dan Conway [was] approaching fifty. He [had] the square, stolid, stubborn face of a tough freight engineer, rather than a company president; the face of a fighter, with a young, tanned skin and graying hair. He [had] taken over a shaky little railroad in Arizona, a road whose net revenue [was] less than that of a successful grocery store, and he [had] built it into the best railroad of the Southwest. He spoke little, seldom read books, [had] never gone to college. The whole sphere of human endeavors, with one exception, left him blankly indifferent; he [had] no touch of that which people called culture. But he {knew} railroads.

She sat looking at him, wondering what it [was] that [had] defeated a man of this kind; she {knew} that it [was] not James Taggart.

She saw him looking at her, as if he [were] struggling with a question mark of his own. Then he smiled, and she saw, incredulously, that the smile held sadness and pity.

The man who entered [was] a stranger. He [was] young, tall, and something about him suggested violence, though she [could] not say what it was, because the first trait one grasped about him [was] a quality of self-control that {seemed} almost arrogant. He [had] dark eyes, disheveled hair, and his clothes [were] expensive, but worn as if he [did] not care or notice what he wore.

Somewhere within her, under the numbness that held her still to receive the lashing, she {felt} a small point of pain, hot like the pain of scalding. She {wanted} to tell him of the years she [had] spent looking for men such as he to work with; she {wanted} to tell him that his enemies [were] hers, that she [was] fighting the same battle; she {wanted} to cry to him: I[’m] not one of them! But she {knew} that she [could] not do it. She bore the responsibility for Taggart Transcontinental and for everything done in its name; she [had] no right to justify herself now.

She {watched} his tall figure moving across the office. The office suited him; it contained nothing but the few pieces of furniture he needed, all of them harshly simplified down to their essential purpose, all of them exorbitantly expensive in the quality of materials and the skill of design. The room {looked} like a motor—a motor held within the glass case of broad windows. But she {noticed} one astonishing detail: a vase of jade that stood on top of a filing cabinet. The vase [was] a solid, dark green stone carved into plain surfaces; the texture of its smooth curves provoked an irresistible desire to touch it. It {seemed} startling in that office, incongruous with the sternness of the rest: it [was] a touch of sensuality.

I noticed that there’s a lot of boring verbs. I see one in most sentences.

I’m going to practice finding the interesting verbs. Square brackets mean Im sure and curly brackets mean im unsure. Bolds are mine:

Dan Conway was approaching fifty. He {had} the square, stolid, stubborn face of a tough freight engineer, rather than a company president; the face of a fighter, with a young, tanned skin and graying hair. He had taken over a shaky little railroad in Arizona, a road whose net revenue was less than that of a successful grocery store, and he had built it into the best railroad of the Southwest. He [spoke] little, seldom [read] books, had never gone to college. The whole sphere of human endeavors, with one exception, [left] him blankly indifferent; he {had} no touch of that which people {called} culture. But he {knew} railroads.

She [sat] looking at him, wondering what it was that had defeated a man of this kind; she {knew} that it was not James Taggart.

She {saw} him looking at her, as if he were struggling with a question mark of his own. Then he [smiled], and she {saw}, incredulously, that the smile [held] sadness and pity.

The man who [entered] was a stranger. He was young, tall, and something about him {suggested} violence, though she could not say what it was, because the first trait one [grasped] about him was a quality of self-control that {seemed} almost arrogant. He {had} dark eyes, disheveled hair, and his clothes were expensive, but {worn} as if he did not care or notice what he wore.

Somewhere within her, under the numbness that [held] her still to receive the lashing, she {felt} a small point of pain, hot like the pain of scalding. She {wanted} to tell him of the years she had spent looking for men such as he to work with; she {wanted} to tell him that his enemies were hers, that she was fighting the same battle; she {wanted} to cry to him: I’m not one of them! But she {knew} that she could not do it. She [bore] the responsibility for Taggart Transcontinental and for everything done in its name; she {had} no right to justify herself now.

She {watched} his tall figure moving across the office. The office [suited] him; it [contained] nothing but the few pieces of furniture he {needed}, all of them harshly {simplified} down to their essential purpose, all of them exorbitantly expensive in the quality of materials and the skill of design. The room {looked} like a motor—a motor {held} within the glass case of broad windows. But she {noticed} one astonishing detail: a vase of jade that {stood} on top of a filing cabinet. The vase was a solid, dark green stone {carved} into plain surfaces; the texture of its smooth curves [provoked] an irresistible desire to touch it. It {seemed} startling in that office, incongruous with the sternness of the rest: it was a touch of sensuality.

Some of the verbs like watched, looked, noticed, wanted, knew, had, seemed, and saw didn’t sound as interesting as run, cook, sing, dance. Cuz of that I wasn’t sure if they counted.

Some of verbs in the last quote sounded like infinitives so I wasn’t sure. They were: needed(2nd sentence), simplified(2nd sentence), held(3rd sentence), stood(4th sentence), and carved(5th sentence).

I was trying to practice relative pronouns, but I think they’re too hard for me to find. They’re hard cuz I don’t know sometimes if the relative pronoun is actually a subordinating conjunction or not. I also don’t know if a sentence is a simple sentence or a complex sentence most of the time. Like it’s hard to see the conjunction and the verbs and subjects of the sentence.

I figured if I practice simple sentences and finding their verb, subject, and object/complement then maybe I could move on to complex sentences and analyze those too.

I’m gonna practice the first two steps of analyzing a simple sentence(quotes below are from FI grammar article):

Step 1 – Verb

The first step for analyzing a sentence is finding the verb . The verbs in the examples are “threw” and “is”.

Step 2 – Subject

Step two is finding the subject . The subject is the noun that does the action or has the link . The subject is always a noun, and it’s the noun that does the verb.

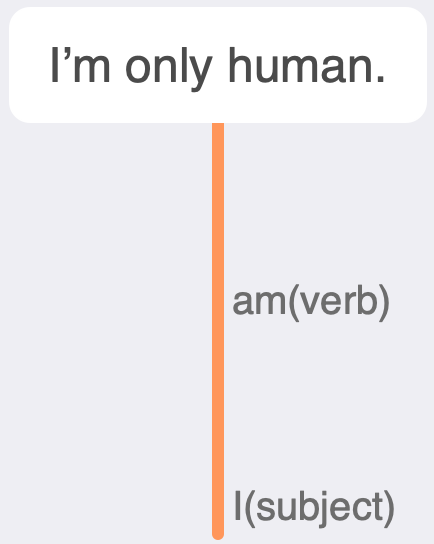

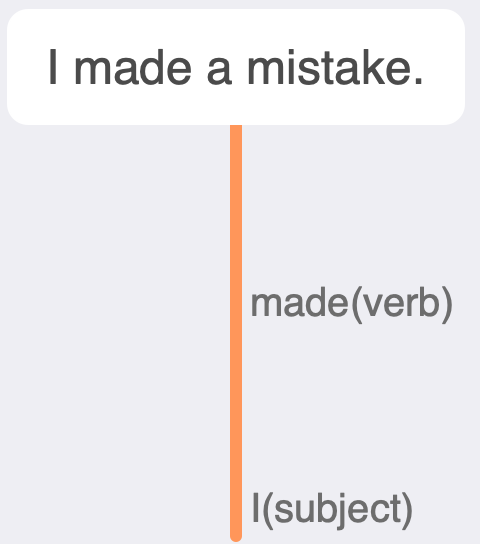

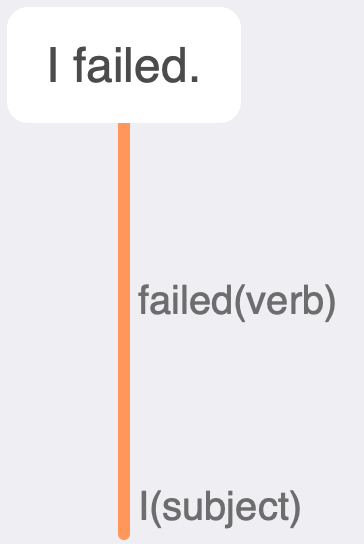

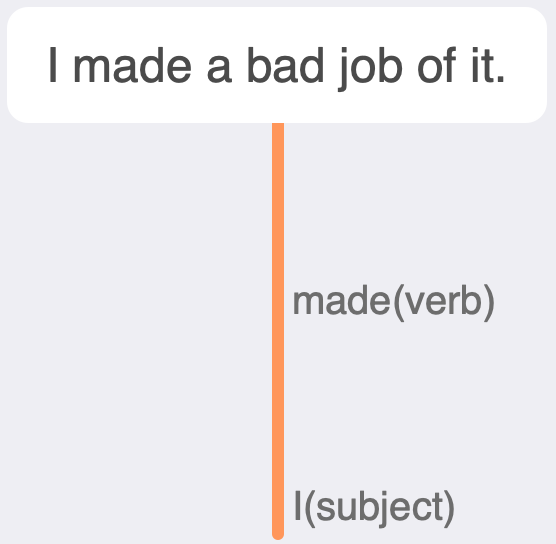

I’m gonna practice step 1 and 2 using sentences from Atlas Shrugged(quotes below are from ch. 5 of part 1):

“That’s true. I don’t understand and probably never shall. I am merely beginning to see part of it.”

“They’re rotten fools, but in this case their only crime was that they trusted you. They trusted your name and your honor.”

They considered knowledge superfluous and judgment inessential.

“No, not exactly. But suppose I slipped up? I’m only human. I made a mistake. I failed. I made a bad job of it.”

I noticed some big looking sentences(w/ coordinating conjunctions, infinitives, and prepositional phrases) can still be analyzed as simple sentences.

Im gonna practice step one and two while reading. After that I want to post about finding the object/complement.

I was confused about relative pronouns and subordinating conjunctions yesterday so I looked them up. The grammar tree video in Videos: Grammar and Analyzing Text has good explanations on that stuff.

Yes, I would recommend practicing simple sentences first. I would also recommend learning relative pronouns/adverbs after conjunctions/complex sentences.

Thats cool. I’ll take a look at that video.

That sounds good. I’ll try to work on both simple sentences and the more complicated stuff

I’m gonna practice step one, two, and three of analyzing a sentence. Here’s step three from the FI grammar article:

Step 3 – Object or Complement

Finding the object or complement is step three. Look to the right of the verb. Finding that there is no object is fine too.

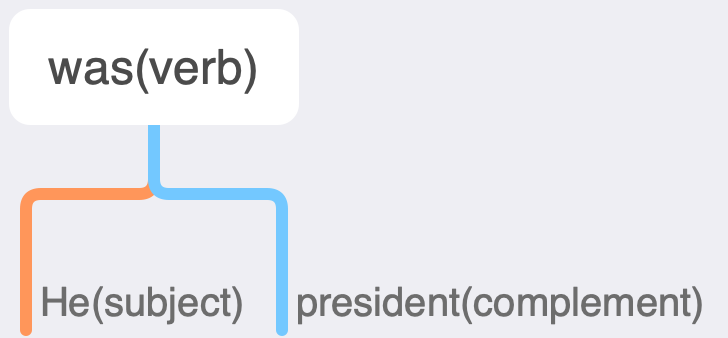

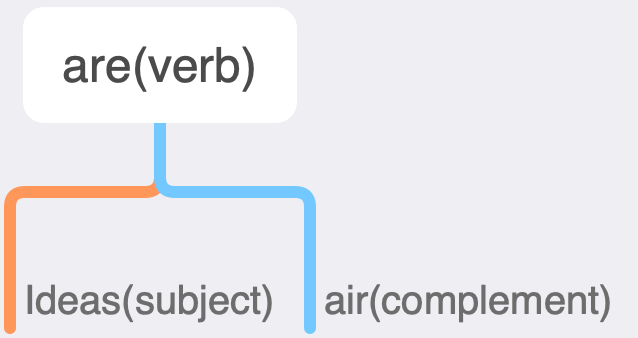

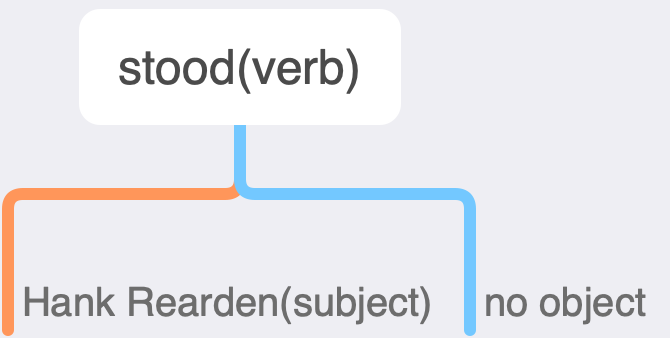

I’m gonna practice on sentences from Atlas Shrugged(quotes below are from ch. 6 of part 1):

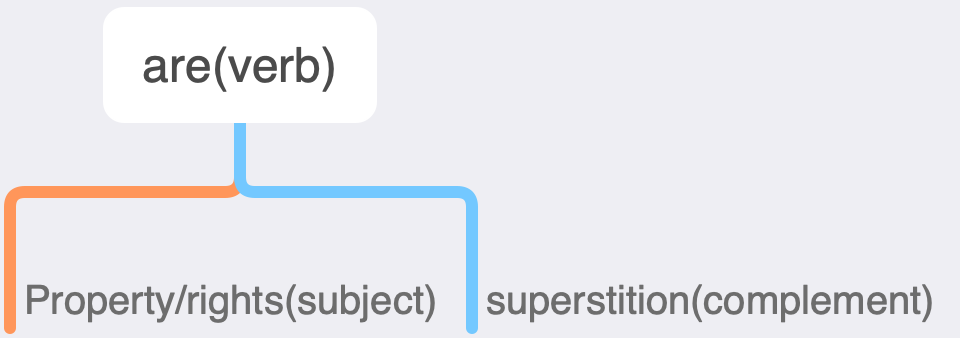

Property rights are a superstition.

I don’t know if “property” or “rights” is the subject. I know though that they could be the subject.

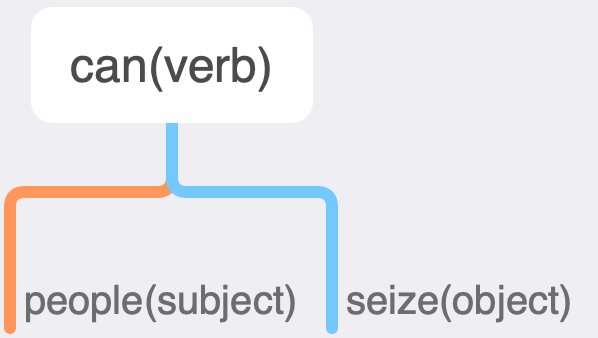

The people can seize it at any moment.

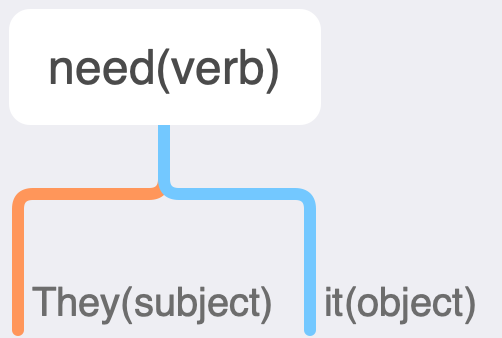

They need it.

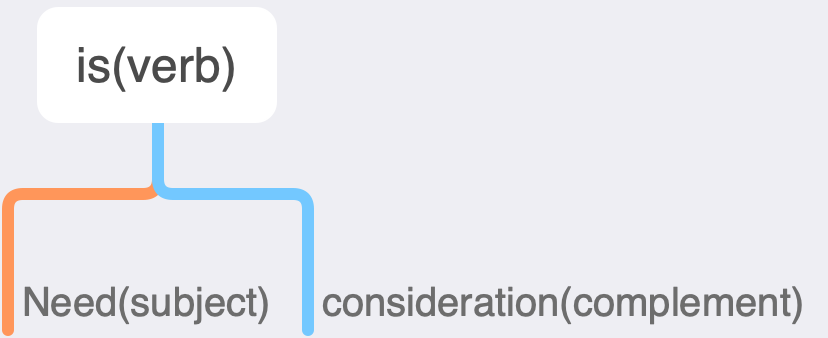

Need is the only consideration.

He was the president of Friends of Global Progress.

Ideas are just hot air.

Hank Rearden stood at a window in a dim recess at the end of the drawing room.

I think “Hank Reardan” is the subject. I’m not too sure why tho. I think Hank Reardan is a phrase that talks about one person. The phrase is the subject of the sentence.

Yes one of them is the subject. One of them modifies the other. Try to think whether “property rights” mean:

- property of rights, or

- rights of property

So is “property rights” a type of property, a thing you own, or a type of right, a thing or act you’re entitled to. If you can figure out what “property rights” means, can you figure out which is the subject?

You can think about “Hank Rearden” as one thing, one node in the tree.

Were you uncertain because “Hank Rearden” is two words?

Thats so cool. Ok I think I get it

Oh yeah I think it’s a type of right. It’s like human rights or civil rights. I know the first part of those phrases may be adjectives, but I know we’re talking about rights when the phrases are brought up.

I think since “property” is describing what kind of rights are being talked about, “rights” is the subject. I would put “property” as a child node of “rights.”

Yeah, I grouped them when I was writing the tree, but then I was just like why? Why am I treating the two words as one?

Yes. The thing is both are nouns, but “property” is still acting as an adjective, it’s telling us what kind of rights. Other examples are “vacation home” and “baseball hat.” But when it’s done improperly it’s called noun pileup (see my notes on it here) like: “bank rate rise leak probe.”

Whenever only “Hank” or “Rearden” is used in AS it’s actually a shorthand for “Hank Rearden”, they’re always referring to the specific person which is Hank Rearden. Compare it with “big house.” “Big” and “house” are different concepts. “Big” can apply to many things. “House” can have many modifiers. “Hank” and “Rearden” are really the same thing. You could say “Rearden” modifies “Hank” so it tells you which “Hank” we are talking about, or the other way around. But that isn’t helpful. The words are so closely related I don’t think it’s worthwhile to give them separate nodes.