I got 1 question wrong on my negligence quiz:

A college student was walking down the street eating a banana. When he finished the banana, he threw the peel in a garbage can. Soon after, a sanitation worker came and emptied the garbage can, dropping the banana peel onto the sidewalk in the process. A passerby stepped on the peel, slipped, and broke her hip.

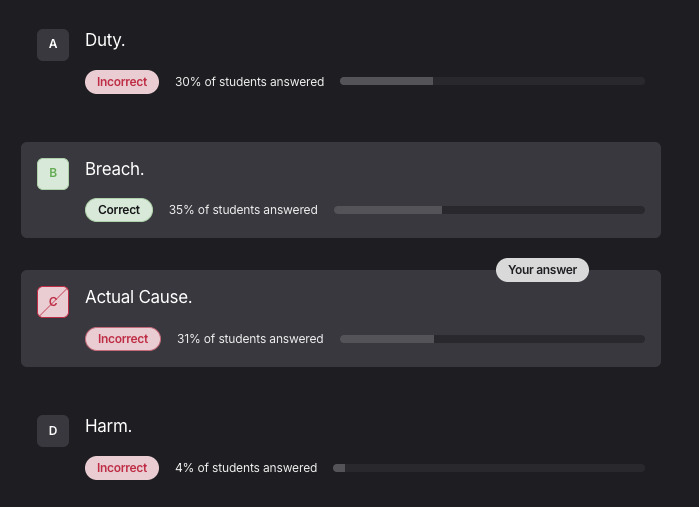

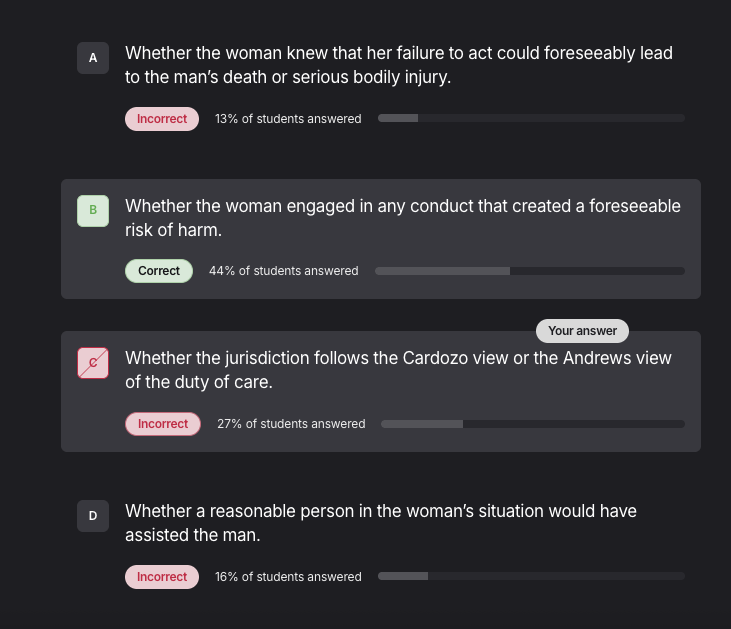

If the passerby sues the student for negligence, on which of the following essential elements of negligence will the passerby be least likely to prevail?

I thought the issue would be actual cause. To me the banana falling out of the trash can because of the sanitation worker seemed too far removed to blame the student.

The question does say least likely, so it could be all of them are kinda unlikely (except harm) its just breach is the least likely out of all of them. Since he does owe a duty of care to others (I think), he did play a part in this banana slipping ordeal, and she was actually harmed. However, he did not really breach his duty to the lady. The sanitation worked did. From the explanation:

Answer option B is correct. The basic elements of negligence are that the actor owes the victim a duty to conform to a standard of care, and the actor breaches that duty, actually and proximately causing the victim harm. In general, an actor breaches a duty owed to a victim by failing to follow the standard of care, or, in other words, by failing to behave as a reasonably prudent person would under the circumstances. Here, by putting the banana peel in the garbage can as soon as he finished eating the banana, the student seems to have done everything a reasonable person could have been expected to do in these circumstances to prevent a passerby from slipping on the banana peel. Because the student almost certainly acted as an ordinary, reasonable, prudent person would have, the passerby will not be able to establish a breach of the duty of care.

Answer option A is incorrect, because the student most likely did have a duty to dispose of his banana peel with reasonable care. A duty of care generally arises if it is reasonably foreseeable that an actor’s failure to conform to the applicable standard of care could injure someone. Here, it seems eminently foreseeable that, if the student did not properly dispose of the banana peel, someone could slip on it and suffer injury. The student owed this duty to the other people using the sidewalk at the time he threw out the banana peel and also to those people, like the passerby, who used the sidewalk soon after him.

Answer option C is incorrect. Generally, the element of actual causation is satisfied if the victim’s injury would not have occurred but for the actor’s conduct. Here, had the student not deposited the banana peel in the trash can, the sanitation worker would not have emptied the peel out onto the sidewalk. Had the peel not been on the sidewalk, the passerby would not have been injured. Accordingly, actual causation is satisfied here.

Note that it is also possible that the passerby would fail on the element of proximate cause, because it might not be reasonably foreseeable that a worker would drop the peel and that it would cause an injury. However, proximate cause is not listed as a possible answer option; of the listed elements, the passerby’s clearest weak spot is on the element of breach.

Ok. I forgot about the proximate cause part. Yes, he played a part in the actual cause of the issue, but there was no proximate cause.