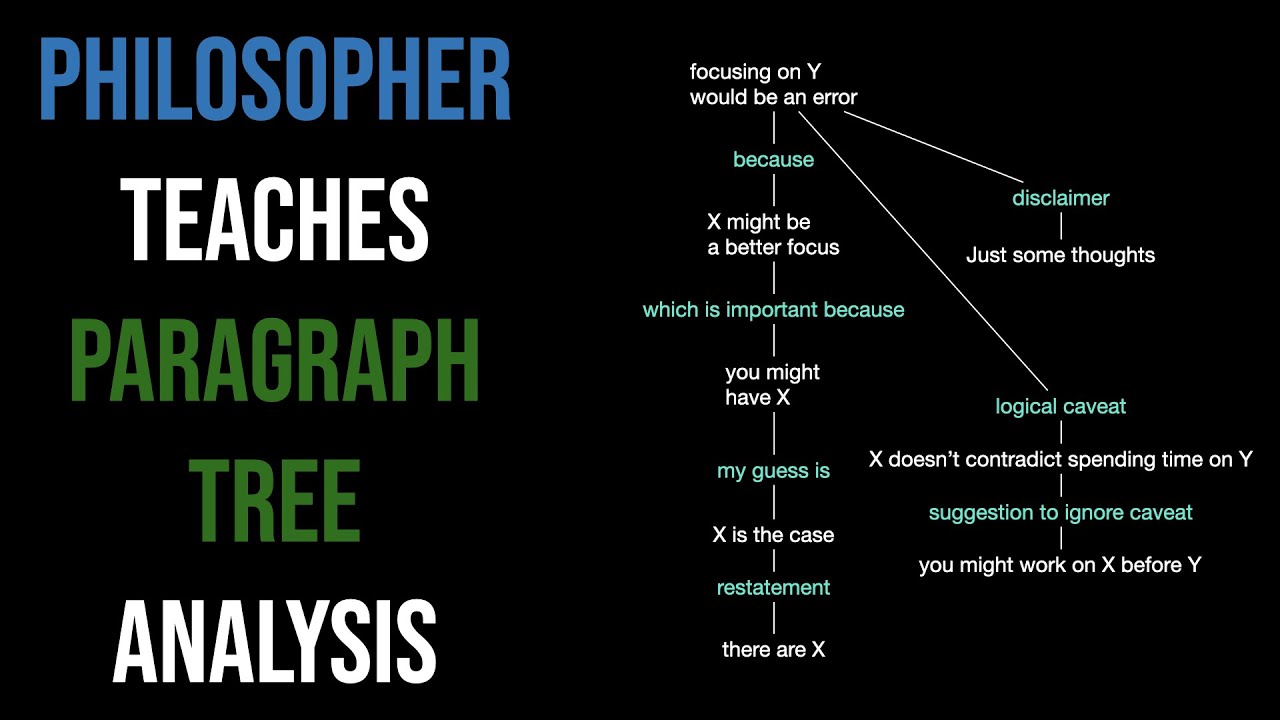

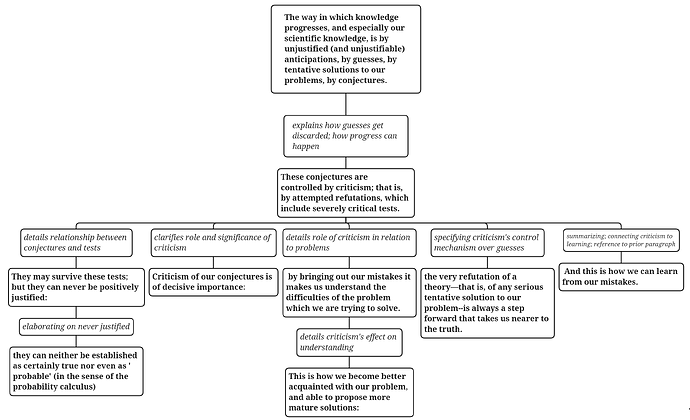

Partial notes on paragraph trees:

- Make a list of the clauses/sentences that are going to be individual nodes.

- Sort the list of clauses/sentences into two groups: important ideas (possible main ideas) and unimportant ideas (details/modifiers)

- Find the main idea, which will be the root of the tree

- Simplify and look for structure. You can use variables to stand in for phrases.

- Root = conclusion. The conclusion is the integration of the parts (arguments) into the whole.

- Organize into nodes and consider the relationship between nodes. Relationship explanations can be their own nodes. Color code nodes by type.

Examples of relationship node connections:

- Detail

• extra information, similar to a modifier - Comparison

• two child nodes (more than two could also work) - Result

• further elaboration

- Restating thesis positively

- Explanation for knowledge

- Explanation for reason

- Explanation for reason

- Evidence/proof

- Elaboration: intelligence comes from computation not special tissue

- ADDITION: again, also, and, besides, finally, further, last, moreover, equally important, furthermore, in addition, likewise

- CLARIFICATION: as a matter of fact, clearly, evidently, in fact, too, obviously, in other words, of course

- COMPARISON: also, likewise, in like manner, similarly, both/and

- CONTRAST: after all, although, conversely, at the same time, however, but, for all that, still, in spite of, yet, nevertheless, in contrast, on the contrary, on the one hand, on the other hand, notwithstanding

- EXEMPLIFICATION or EXAMPLE: for example, for instance, that is, thus, including

- LOCATION or SPATIAL ORDER: above, adjacent to, below, beyond, close by, elsewhere, inside, nearby, next to, opposite, within, without

- CAUSE / EFFECT or CONDITION / CONCLUSION: accordingly, as a result, because, then, hence, in short, consequently, thus, therefore

- SUMMARY: in brief, in conclusion, in short, to sum up, on the whole, to summarize

- TIME: after, after a short time, afterward, before, during, of late, at last, at that time, immediately, formerly, while, presently, since, shortly, now, thereupon, until, temporarily

ELLO.

- PARAPHRASE: two sentences that have the same meaning

- ENTAILMENT: the truth of one sentence entails (or implies) the truth of the other sentence

- TO ADD OR SHOW SEQUENCE: again; also; besides; equally important; finally; first, second . . .; further; furthermore; in addition; in the first place; last; moreover; next; still; then; too

- TO GIVE ADDITIONAL INFORMATION OR SUPPORT: additionally, again, also, equally important, furthermore, in addition to, in the first place, incidentally, moreover, more so, next, otherwise, too

- TO SHOW LOGIC: also, as a result, because of, consequently, for this reason, hence, however, otherwise, then, therefore, thus

Note: Attributes of a clause that include establishing common ground with the audience and helping build up an argument suggest that the clause is a premise of an argument. The premise of an argument belongs somewhere lower in the paragraph tree than the conclusion.

- Big idea/statement of topic

- Partial reason for conclusion

- Furter claim/elaboration/sub-point

Tutoring Max #6 - YouTube

Note: Most likely parents of a sentence/clause are the main/root sentence or the immediately preceding sentence. That’s a starting point for identifying parent child relationships between nodes.

Tutoring Max #6 - YouTube - Sub-topic: more detailed issue within the same area

- Example: providing detail/elaboration, answering how question

- However, contrast, provide commentary, additional info

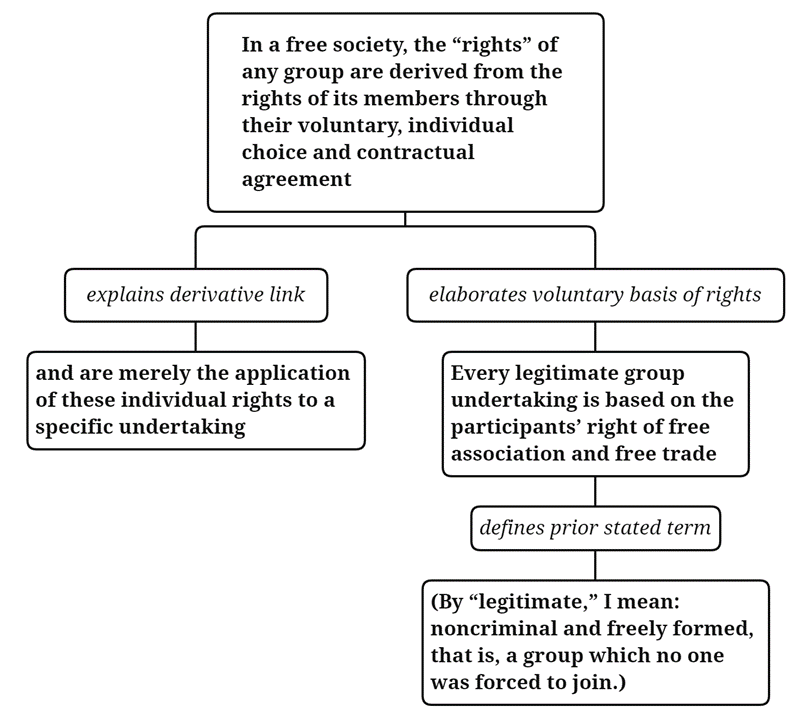

In a free society, the “rights” of any group are derived from the rights of its members through their voluntary, individual choice and contractual agreement, and are merely the application of these individual rights to a specific undertaking. Every legitimate group undertaking is based on the participants’ right of free association and free trade. (By “legitimate,” I mean: noncriminal and freely formed, that is, a group which no one was forced to join.)

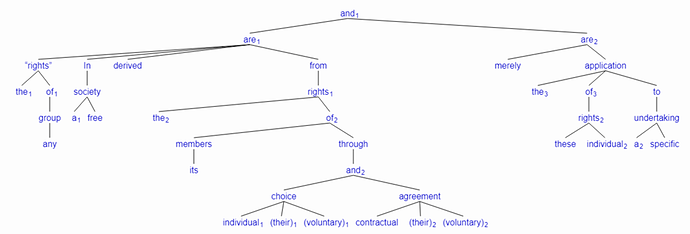

- In a free society, the “rights” of any group are derived from the rights of its members through their voluntary, individual choice and contractual agreement, and are merely the application of these individual rights to a specific undertaking.

- In a free society, the “rights” of any group are derived from the rights of its members through their voluntary, individual choice and contractual agreement

o **conclusion; in context - and are merely the application of these individual rights to a specific undertaking.

o **explains derivative link

- Every legitimate group undertaking is based on the participants’ right of free association and free trade.

o **elaborates voluntary basis of rights - (By “legitimate,” I mean: noncriminal and freely formed, that is, a group which no one was forced to join.)

o **defines a prior stated term

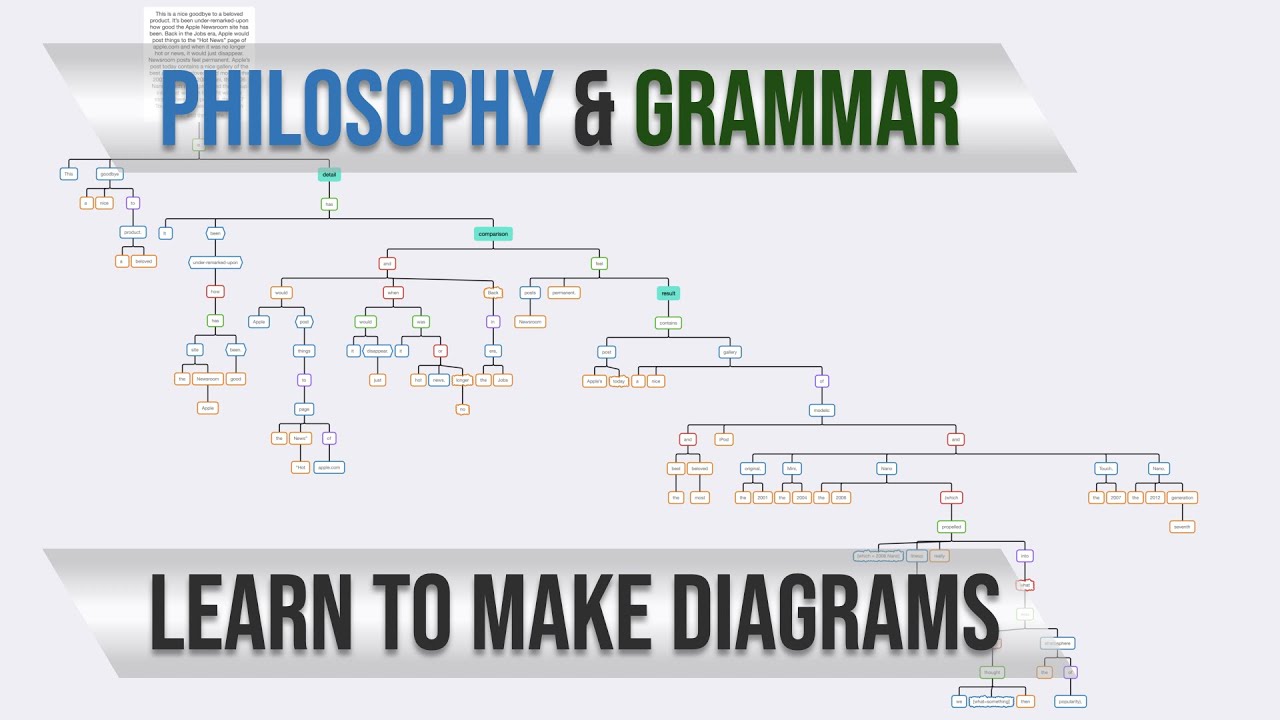

Topic Sentence Grammar Analysis:

[and [are [“rights” [the] [of [group [any]]]] [In [society [a] [free]]] [derived] [from [rights [the] [of [members [its]] [through [and [choice [individual] [(their)] [(voluntary)]] [agreement [contractual] [(their)] [(voluntary)]]]]]]]] [are [merely] [application [the] [of [rights [these] [individual]]] [to [undertaking [a] [specific]]]]]]

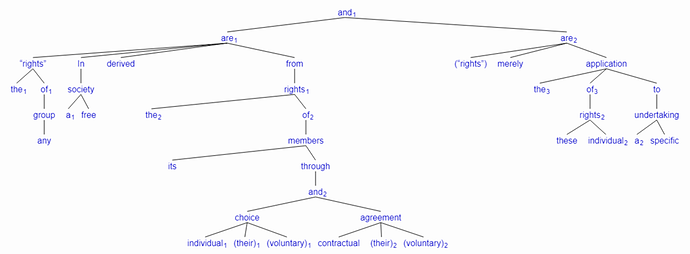

Couple of edits/corrections to grammar tree analysis:

- Added and implied “rights” to the second clause

- Made “members” the parent node of “through” for nested prepositions

[and [are [“rights” [the] [of [group [any]]]] [In [society [a] [free]]] [derived] [from [rights [the] [of [members [its] [through [and [choice [individual] [(their)] [(voluntary)]] [agreement [contractual] [(their)] [(voluntary)]]]]]]]]] [are [(“rights”)] [merely] [application [the] [of [rights [these] [individual]]] [to [undertaking [a] [specific]]]]]]

From the preface of Conjectures and Refutations:

The way in which knowledge progresses, and especially our scientific knowledge, is by unjustified (and unjustifiable) anticipations, by guesses, by tentative solutions to our problems, by conjectures. These conjectures are controlled by criticism; that is, by attempted refutations, which include severely critical tests. They may survive these tests; but they can never be positively justified: they can neither be established as certainly true nor even as ‘probable’ (in the sense of the probability calculus). Criticism of our conjectures is of decisive importance: by bringing out our mistakes it makes us understand the difficulties of the problem which we are trying to solve. This is how we become better acquainted with our problem, and able to propose more mature solutions: the very refutation of a theory—that is, of any serious tentative solution to our problem–is always a step forward that takes us nearer to the truth. And this is how we can learn from our mistakes.

GOAL: Just to put a bit more of my thinking on the forum. I wrote this with the thought of practicing thinking out loud and finding errors and gaps in my thinking.

CONTEXT: I wanted to try a free-write version of Feynmann’s blank sheet method for grammar and text analysis.

Free write about Grammar and Text Analysis:

Grammar analysis is part of text analysis.

How does grammar help?

Grammar analysis helps you understand the relationship between words in a sentence. The parts of the sentence that you are trying to understand are the verb, the subject, the object or compliment, modifiers, and conjunctions (in the case of complex/compound sentences). The verb is the best thing to look for first. As you identify the verb you simultaneous identify whether it is an action verb or linking verb. Finding the verb helps split the sentence in half with the first half being the part of the sentence that contains the subject.

Once you have identified the verb and the subject, you look at the subject’s relationship to the rest of words following the verb. If you have a linking verb, you are looking for a sort of equivalency connection between the subject and the complement. The complement can be a noun or an adjective. In the case of adjective complements, the complement can be an aspect, an attribute, or a subset of subject. Noun complements establish a bit more of an equivalency with the subject.

Modifiers of words are often right next to the word they modify and proximity is a good clue, even when there is word separation between modifier and modified. Other than in the case of adjective complements, it helps to look for subject modifiers in the first half of the sentence, as delimited by the verb.

How does grammar fit into text analysis?

Spotting verbs quickly helps you quickly identify the clauses within a sentence. In text analysis, the clauses may be broken apart as separate nodes. The type of verb in sentence gives a big clue about some of the goals of the sentence. Linking verbs can indicate sentences that have a goal of defining something or relating an aspect of something to something else, e.g. relating a concept to an example.

Some additional understanding of verbs, like modal verbs or auxiliary verbs, helps to further clarify the relationship between subject and object/complement. The modal or auxiliary further qualifies the defining relationship between the subject and the rest of the sentence.

For relationships between sentences, you can try to identify whether a subject from a prior sentence is the subject in a following sentence. Or, whether the object or complement of a prior sentence is the subject of the next sentence. Those could be indicators that the follow up sentence is detailing or defining some term or concept from the prior sentence.

Word repetition is a big help in seeing the connection between sentences. The repeated word is can be a concept or idea that being expanded upon. The types of words used to expand upon a subject show something about the inter-sentence relationship. Modifiers on the expand concept show that a sentence is adding details or qualifiers to the concept. That means the sentence is trying to narrow down to a more exact concept. A qualifying sentence acts similar to a modifier word in that is helps classify and categorize which ideas we are talking about and which ones we’re not talking about.

I think the “from” group modifies “derived” not “are”. And the “through” group modifies “rights” not “members” nor “of”. (Do prepositions ever have modifiers?)

Yes but not often.

Source? Preferably a primary source.

Yes. Unfortunately writers are taught to limit word repetition and to intentionally use synonyms. That harms clarity.

In philosophy writing, it can be good give multiple synonyms in one place to give more perspectives on a concept.

But if you are going to refer to the same concept in two separate places, you shouldn’t use a brand new word in the second case. You should repeat a word to help the reader know it’s the same concept as before. If you use a synonym, he might miss the connection, or he might think that the change in word indicates there’s a difference.

I picked up the term second hand from a few different places over time but I don’t remember if I ever saw anything from Feynman himself about the method. After looking into it a bit, I think it might not be something that Feynman ever said he did or advocated doing. It seems like it could be something that some people inferred he was doing from looking at his notes.

It would probably be better for me to call it the blank sheet recall method, or something, as long as I don’t have a good reference about it from Feynman. I wasn’t really trying copying a specific method either. It was more a label I had in mind for a range of free-writing exercises. I referenced the term based on my recollection from second-hand sources to add a little more context to the style free-write that I was attempting.

I want to avoid misattribution and this is a good example of how easily I can fall into that trap. One partial solution might be to try to keep my communication simpler. I can also try to avoid overconfident/unqualified attributions and not do name-dropping. It could be an automatized social thing that I have going on.

Second-hand references to Feynman technique:

I also want to emphasize that I don’t know much about how proper attribution works.

GOAL: Think outside myself, in writing, about grammar feedback.

I briefly thought about going with each of those variations of the tree.

On “from” modifying “derived”:

I didn’t have confidence in putting the “from” group below “are”. I feel like I don’t have a conceptual understanding of the grammar trees that have helper verbs. I have sort of been following a rule that the linking verb is more important to the grammar of the sentence than the main verb and that the main verb is grammatically limited to being a modifier of the helper verb. The linking verb is more central grammatically because it defines the type of sentence, in terms of linking vs action; that part makes sense. I also understand that the main verb can be more conceptually central to the meaning of the sentence. In this case, I have some notion of “derived” being the more important verb conceptually but “are” being the more important verb grammatically.

In sentences with linking verbs, complements are always required.

EDIT (fixing link): From ET’s grammar article Fallible Ideas – Grammar :

What’s the difference between an object and a complement? Objects go with action verbs, they’re always nouns, and they’re sometimes optional. Complements go with linking verbs, they’re nouns or adjectives, and they’re always required.

If the prepositional phrases should be nested below “derived” then “derived” is the complement. One meaning of the sentence is that group rights come from group members rights. A slightly different, more direct, meaning is that group rights are derivative. Directly linking group rights to what they are derived from misses an important meaning of the sentence.

I think I was hung up on thinking that “derived”, in its capacity as a main verb, had to be a modifier of “are”. And that if “derived” is a modifier of “are” then it’s an adverb, which would mean it can’t be the complement of the sentence because the complement is either an adjective or a noun.

But, “derived” can actually be a past tense verb or a past participle, which would mean it’s a noun. So, “derived” can be the complement by being a noun. With that in mind, I think the subject, “rights”, is being linked directly to the idea “derived”. I think this makes sense to me now.

Did it make sense to think of a prepositional phrase as a complement?

Prepositional phrases are modifiers and they can act as adverbs or adjectives. Prepositional phrases usually modify a word that they are right next to.

From Grammar article:

In “John sat in his chair.”, the preposition is “in” and its noun is “chair”. The prepositional phrase “in his chair” is an adverb modifying “sat”. It tells us what John sat in.

I can see how the prepositional phrase there is modifying “sat”.

Examples of prepositional phrases as complements:

In the sentence, “John is in his chair.”, “in his chair” must be modifying “John”, since complements are required and they are either a noun or an adjective. That combination precludes “in his chair” from modifying “is”, because that would make the prepositional phrase an adverb. “In his chair” is the state that John is in; an aspect/attribute of who he is at the moment.

Another example of a prepositional phrase as a complement would be “These books are in the public domain.” The subject is “books”, the linking verb is “are”, and “in the public domain” is a prepositional phrase that modifies “books”. “In the public domain” is an attribute of the books. It’s a qualifier on the kind or type of books.

Some conceptual corrections/takeaways:

- “derived” wasn’t a main verb or any kind of verb, it was a noun

- prepositional phrases can be complements

- use the meaning of sentence as input for figuring out grammar of the sentence

Additional questions for me to research:

Can main verbs can be complements? I think that would mean that a main verb was grammatically an adjective. Can that happen?

Do main verbs always act as modifiers on auxiliary verbs?

None of that is how I decided (it’s also confusing because you’re mixing some mainstream grammar perspective with some dependency grammar perspective).

I just thought about what modifies (provides more information about) what. I think the “from” clause tells you what the rights are derived from, not what they are from. I thought it was elaborating on their derivation not their existence.

And yeah “derived” is the complement.

Prepositional phrases after verbs are usually modifiers/adverbs, but yes in your example where the prepositional phrase is immediately after a linking verb (“John is in his chair.”) then the prepositional phrase is a complement.

I couldn’t tell from your tree that you thought the prepositional phrase was the complement. I assumed you were using it as a modifier. Maybe you should label some relationships or parts of speech in your trees when it might be unclear, especially an object or complement. I don’t think you keep the child ordering consistent as a hint either (I have a policy to put subject first, then object or complement has second priority, and modifiers go later. I’ve also color coded parts of speech in a bunch of videos.)

It being a (verbal or verb-derived) noun, and it being a “main verb” are compatible. You’re using “main verb” to refer to a viewpoint where there are auxiliary/helper verbs and “main” verbs (which is a problematic name). Some IMO more clear terminology is finite and non-finite verb, and the non-finite verbs always function as some other part of speech while also retaining some characteristics of verbs. A clause has only one finite verb which is always the root of the tree for that clause (if we ignore clause conjunctions as separate), but for some reason that is not the “main” verb according to a lot of people. All the other “verbs” are non-finite (gerunds, participles, infinitives) and partly act as some other part of speech. The finite verb is usually (always?) the first verb (from left to right) when you get to the group of words you could think of as forming the verb (like in “had been eating” it’s the left most verb that is finite).

I basically stopped thinking in terms of main and auxiliary verbs and just look at finite and non-finite which matches the tree structure better too (I don’t want to call a child “main” and a root or parent “auxiliary” or “helper”).

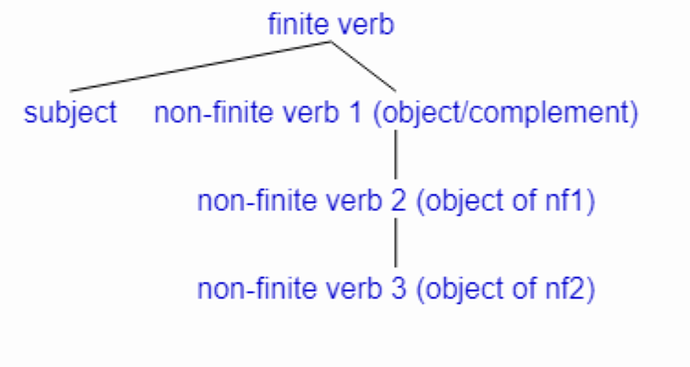

When you see several consecutive words like “had been eating”, in general the first one is the finite verb and clause root, and each other verb is the non-finite object/complement of the one before it.

So if you see: “W X Y Z” (each letter being a finite or non-finite verb)

Then expect that W is finite (and leads the clause rather than being the object or complement of anything), X is the object (or complement) of W, Y is the object of X, and Z is the object of Y.

And when you draw it as a tree, they just go in order. Each word further right goes one level lower in the tree.

I think that I had the same initial intuition but overrode it with the above mentioned confused reasoning.

I will try to remember that child ordering to be more consistent. I agree that labelling or color coding would be beneficial as well.

Tree ordering priority:

- Subject

- Object/Complement

- Modifiers

It didn’t occur to me that “derived” might be considered anything but a modifier of “are”. I made that assumption and ran with it. Good to see how many follow on mistakes that led to, including ambiguity in how accurate my tree was. It was worse than it appeared to you because you though I had at least recognized that “derived” was the complement and only failed to see what the “from” group was modifying. But, I actually misunderstood multiple aspects of “derived” and the “from” group.

I need to do some research on how to make better, more advanced, trees. I don’t know how to color code with ironcreek.net jsSyntaxTrees or XMind. I haven’t tried with jsSyntaxTrees yet. I have tried with XMind and I don’t think I can with the free version. I should revisit learning about other tree diagram software.

Big takeaway for me:

Review, practice, and research the differences and workings of finite verbs vs non-finite verbs. Aim to make this one of my main conceptual and intuitive ways of understanding verbs. Try to translate other grammar sources into the dependency grammar framework for better understanding.

Mac or PC? No money to pay for something?

“subject” W X Y Z

“subject” “finite verb” “non-finite verb 1” “non-finite verb 2” “non-finite verb 3”.

[“finite verb” [subject] [“non-finite verb 1 (object/complement)” [“non-finite verb 2 (object of nf1)” [“non-finite verb 3 (object of nf2)”]]] ]

It’s actually a bit of a flaw in English.

Earlier in the sentence and higher in the tree both correspond to grammatical importance. So that’s good.

But conceptual importance may not match the grammatical importance or word ordering. A more conceptually important word can be later in the sentence, lower in the tree, and less grammatically emphasized. Those things being out of sync is a negative and is maybe one of the reasons for all the confusion.

There is a writing tip that if what’s grammatically emphasized in your sentence doesn’t match what you’re trying to emphasize, then you should rewrite the sentence. Peikoff said something about that.

In “had been eating”, the action of eating usually has the most conceptual importance (though there could sometimes be emphasis on one of the other words, like if the timeline was really important to a criminal investigation). But that’s just how English works; you wouldn’t generally rephrase it to try to fix that.

Putting the subject before the verb also doesn’t match the grammatical importance or structure, and sometimes doesn’t match the conceptual importance. And that too has led to confusion like people who look for the subject first when doing grammar, or people who think the subject and verb are equally important (as in constituency grammar).

I’m on PC.

I’m low income right now and pretty frugal but I do have money for a $60/yr subscription (I think that’s what XMind costs). I do think that it would be a bad idea for me to get ten $60/yr software subcriptions. Getting a subsciption would feel like a bit of a commitment but I think it would definitely be worth it if I decide that XMind is good enough to be my go to, comprehensive, tree diagram software. I guess it’s mostly my frugal habits and lack of researching alternatives that has prevented me from buying so far.